The Twenty-first Sunday in Ordinary Time [C]

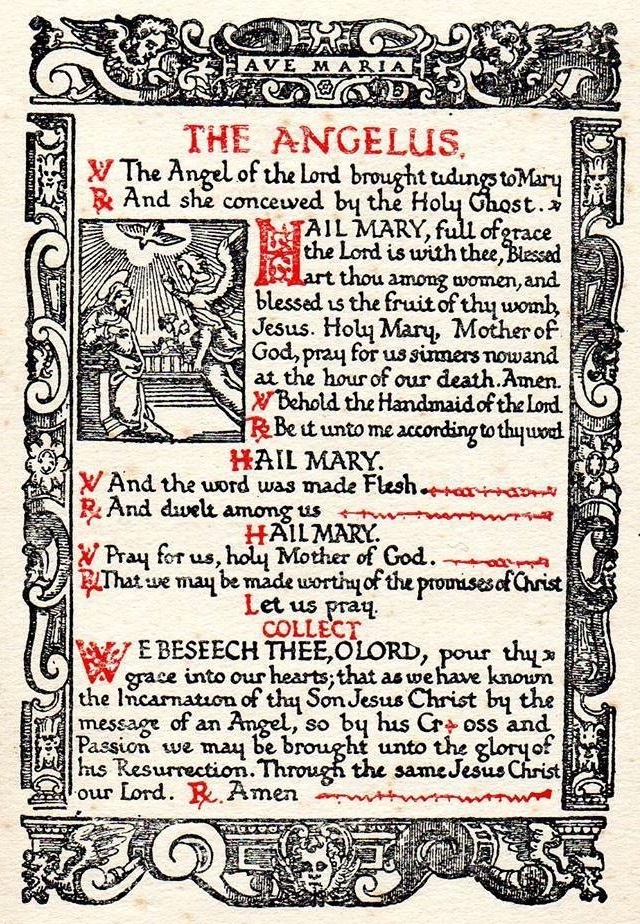

Isaiah 66:18-21 + Hebrews 12:5-7,11-13 + Luke 13:22-30

August 24, 2025

It might be hard to believe, but not everyone loves going to school. In fact, even an enthusiastic student might find something not to like. For some students that might be walking a long distance to school. Growing up, our parents refused to drive my sisters and brother and me to school unless the temperature was below freezing. I looked it up on Google Maps: the distance from our home to the primary school was 0.7 mile. That’s practically a marathon! Actually, most of the time I enjoyed walking to school. But if the weather were ever bad and I complained to my father, he’d just say: “It’s good for you. Builds character.”

Another reason some people don’t like school is the discipline. I attended the public schools in Goddard for twelve years, so I did not have the benefit of Catholic schools, or Catholic schools’ nuns, or Catholic schools’ nuns’ rulers. But given that my elementary education started fifty years ago in a small town in Kansas, our principal still used corporal punishment.

But while punishment can take many forms (some more prudent than others), it’s more important to recognize that punishment itself is just one form of discipline.

+ + +

Discipline has two different forms. The second is punishment, and at times that’s certainly needed: in the classroom, in the home, in civil courts, on the practice field and the court, and at the moment of death. However, you’re going to have a hard time growing in the Christian life if you don’t recognize another form of discipline that’s even more important than punishment.

While the second and lesser form of discipline is punishment, the first and more important form of discipline is what we might call the “trials of training”, as Saint Paul proclaims in today’s Second Reading.

These “trials of training” are not punishment. But they are necessary for success. This is true regarding lots of earthly endeavors. For example, think of a football team. A player might tell his parents that the coach put the team through a “punishing workout”, but the player doesn’t mean that the coach was punishing the team for doing something wrong. Just the opposite: the coach was training them through trials to help them achieve a victory, because success demands the trials of training.

Consider what Saint Paul explains in today’s Second Reading about: first, trials; and then, training.

+ + +

The discipline that prepares for success is a trial. St. Paul writes to the Hebrews about this: “Endure your trials as ‘discipline’; God treats you as sons. For what ‘son’ is there whom his father does not discipline?”

Fathers discipline their children in two different senses. Fathers administer punishment when needed, but they also apply discipline in the first and more important sense, so that their children don’t become soft, and waste their childhood on things like video games and smartphones.

“Endure your trials as ‘discipline’”. These words of St. Paul are spoken to each of us. However, we need to think about the many different kinds of trials that you’re likely to face during your earthly life.

The word “trial” has many meanings. One meaning relates to the courtroom—a courtroom trial—but clearly that’s not what St. Paul is referring to when he insists that the Hebrew Christians ‘endure their trials as discipline’.

Another sense of the word “trial” means a bad experience, as in the phrase “trials and tribulations”. That kind of trial is simply part of life’s constant ups and downs. This is part of what St. Paul is getting at, but there’s still something more specific that he also wants us to think about.

A third sense of the word “trial” is part of the phrase “trial and error”. This kind of “trial” is connected to the simple verb “try”, as in the old adage: “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.” This kind of “trial”—connected to the word “try”—is an important part of our Christian life. How many people never succeed at something because they never try at something, because they don’t want to fail, and don’t want to be a “failure”? They don’t understand that in life on this earth, anything that’s difficult enough to be worth doing will demand your failure, as part of the price for success.

This kind of trial—the “trial” that comes from having to “try, try, again”—is something very simple. It’s like the trial of learning your multiplication tables, or the trial of learning how to drive a stick shift, or the trial of learning how to throw a football accurately to a receiver fifty yards away. This kind of “trial” is a basic building block of success, and that includes success in the Christian life.

+ + +

So this phrase “the trials of training” has two parts: trials and training. St. Paul wrote about trials when he counseled us to “[e]ndure your trials as ‘discipline’”.

But what about training? In today’s Second Reading, St. Paul does refer to discipline as training when he writes to the Hebrews: “At the time, all discipline seems a cause not for joy but for pain, yet later it brings the peaceful fruit of righteousness to those who are trained by it.”

The verb “train”, like the verb “try”, is not very exciting. To train for a new job at work, or for a new position on the team, or for the role of altar server at Holy Mass, is simple. It’s not very exciting and in fact is pretty routine. But routine is also at the heart of success.

Consider an example. Athletes get tired of, and maybe even bored with, running the same drills and plays over, and over, and over again. Why do the same drills and plays have to be run so many times? Most of us know the answer to that question from our experiences in life: the discipline of the “trials of training” make it so that what we’re doing—running a play, solving an equation, driving a stick shift—becomes second-nature, so that we don’t have to think about each and every step.

The problem is that many people don’t think that the trials of training—that the connection between trial, training, and success—has any connection to the entire Christian life: most especially, to Christian prayer, to Christian morality, and to frequent, devout reception of the Sacraments.

+ + +

Many Christians simply think that if you get baptized, and don’t commit mortal sin, that you will go to Heaven. In fact, that is true: if you are baptized, and don’t commit mortal sin, you certainly will go to Heaven. But is that all there is to the Christian life?

If the Christian life amounts to no more than these three steps—get baptized as a baby, don’t commit mortal sin during your life, and from your deathbed go to Heaven—then everything between your day of baptism and your day of death just boils down to avoiding mortal sin. Is that all that the Christian life amounts to? We know that the answer must be “No”, but we might not be sure why the answer is “No”.

If the Christian life on earth did amount to nothing more than avoiding mortal sin, then discipline would only relate to that middle stage of avoiding mortal sin. On the one hand, to avoid falling into sin, we need to be disciplined to become strong enough to resist temptation. But when we do commit sin, then we are disciplined through punishment.

So is that all that discipline is for in the Christian life: to avoid temptation, and to be punished when we do sin? Some Christians actually do reduce discipline to Christian morality, and their Christian life is flat because of it, like a can of pop that’s opened in the evening and tasted the next morning.

+ + +

Discipline is meant to be part of our entire Christian life, including the devout practice of the Sacraments, daily prayer, as well as morality. Nonetheless, all of that discipline in your Christian life has a higher aim: namely, allowing the heart of your Christian life to flourish instead of withering. The heart of your Christian life is life in Christ. Not just a life modeled after Christ’s, but a life lived in Christ, so that Christ lives in you and through you: not just for an hour on the weekend, but flourishing every day of the week, bearing grace into your family, your work, your community, and even your struggles and failures.