Click one of the following for a specific menu:

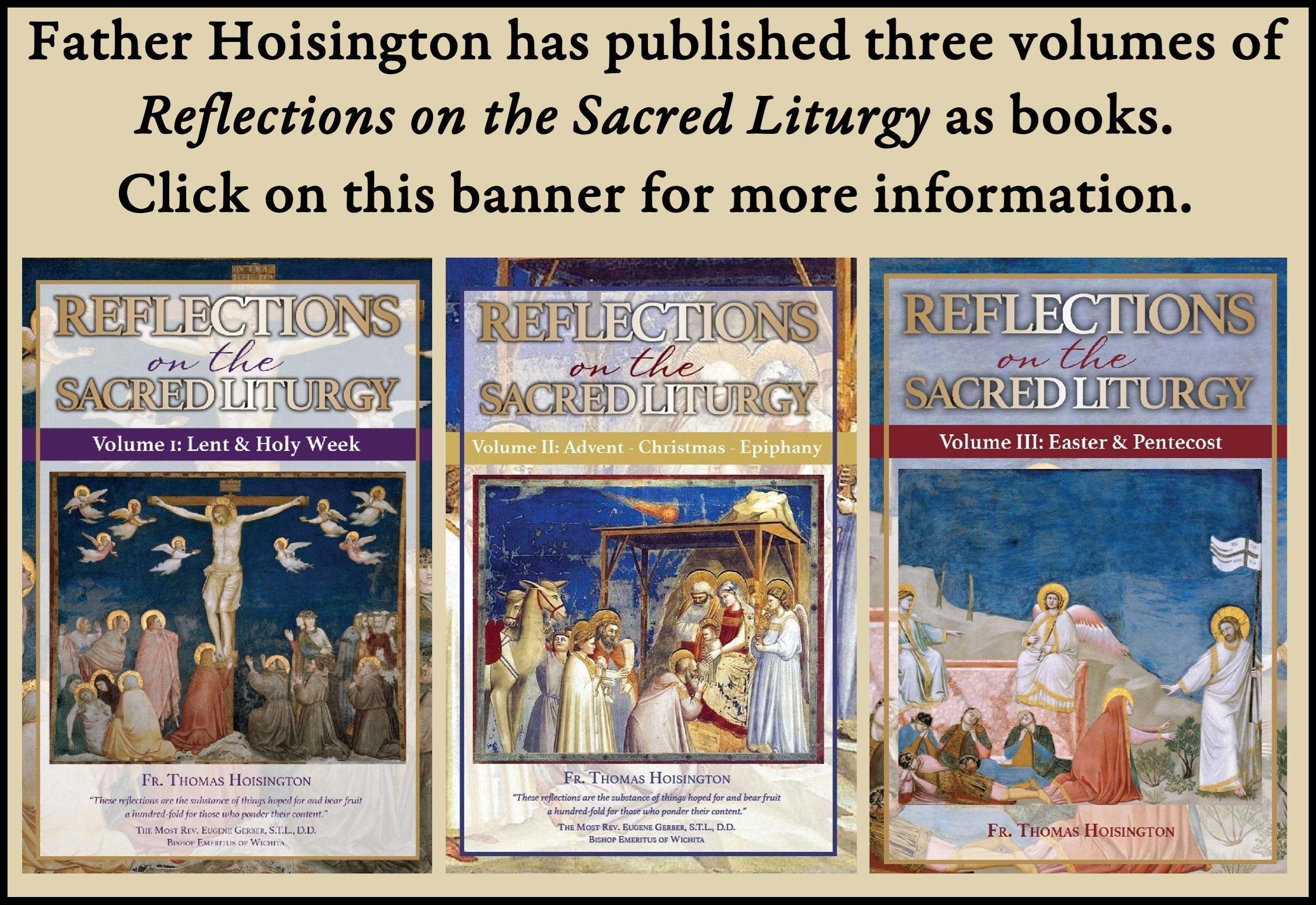

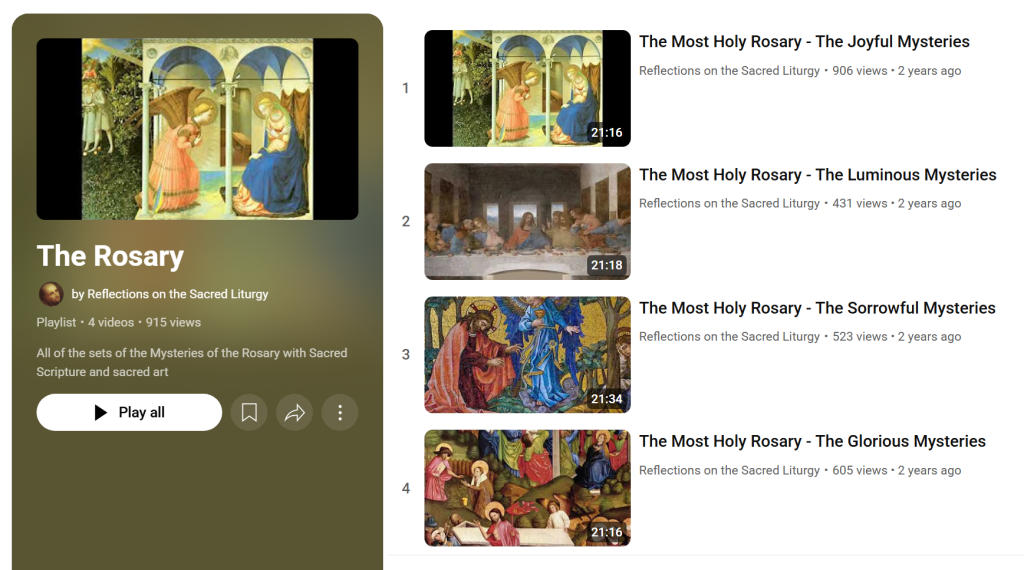

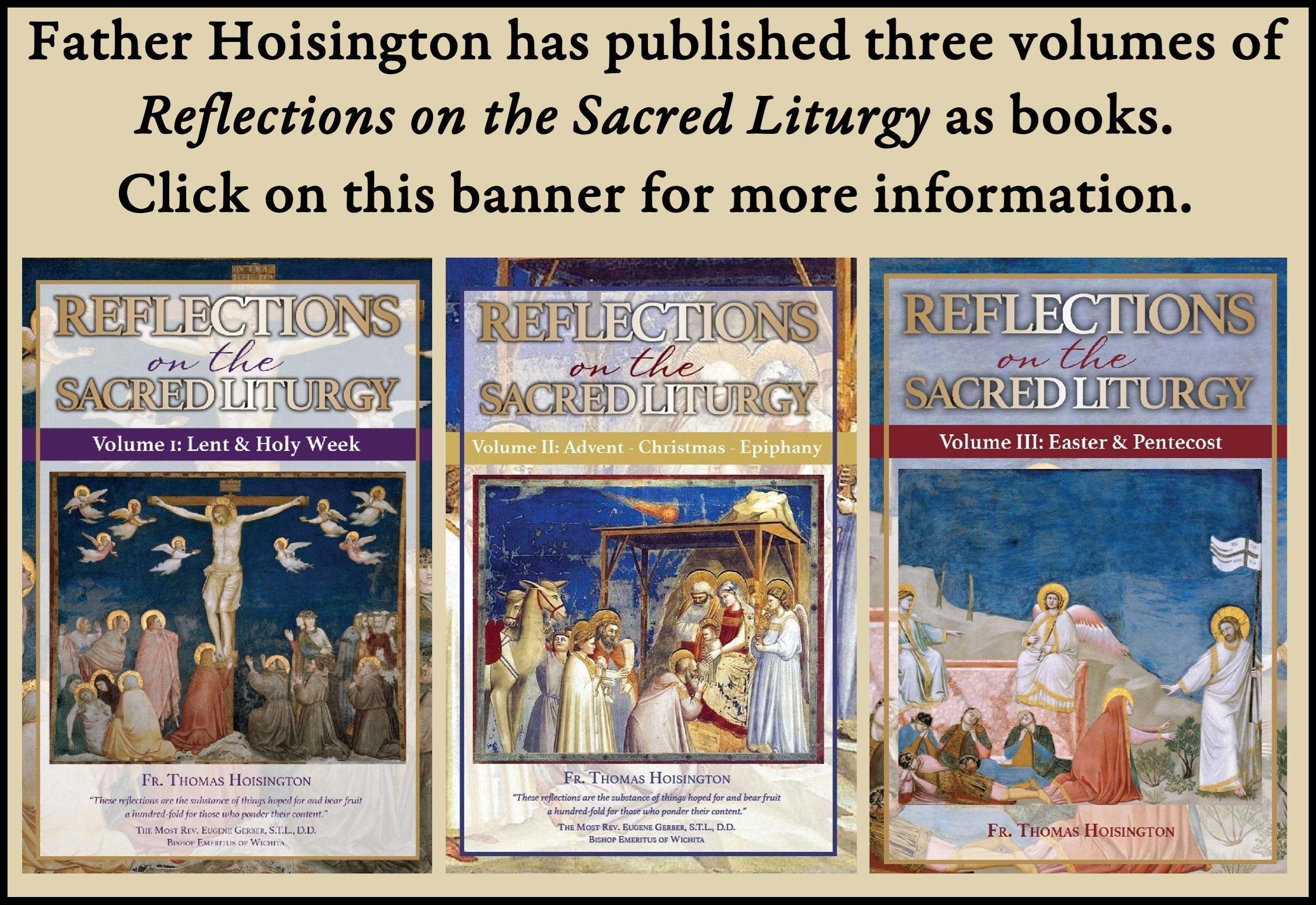

CLICK HERE FOR FATHER HOISINGTON’S

YOUTUBE VIDEOS OF THE ROSARY WITH

SCRIPTURE AND SACRED ART

The Third Sunday of Lent [A]

Exodus 17:3-7 + Romans 5:1-2,5-8 + John 4:5-42

St. Anthony’s Catholic Church, Wellington, KS

March 8, 2026

This year on the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Sundays of Lent, our Gospel passage comes from the Gospel according to Saint John. Saint John’s Gospel account differs from Matthew, Mark, and Luke in many ways. One of the unique things about John, which we will notice during these three Sundays, is that John often expresses double meanings through Jesus’ words and actions.

For example, when Jesus cures a blind man, the evangelist goes out of his way to show how that cure—besides being a physical healing—is also a sign that Jesus can cure a person’s spiritual blindness. Also, in John Jesus speaks with Nicodemus late at night about being “born again”, which Nicodemus misunderstands. Nicodemus goes on and on thinking that Jesus is talking about being physically “born again”, when Jesus is talking about being spiritually born again. In fact, most of the double meanings in John occur when people confuse the worldly and the heavenly. To be honest, that’s a lot like our lives as sinners: we confuse the worldly and the heavenly, putting our focus and attention in life in the wrong place. St. John is trying to shift our attention in the right direction.

So in today’s Gospel passage, St. John the Evangelist describes Jesus as He’s approaching the Samaritan town where Jacob’s well is found. Jesus is “tired from His journey”, and so He sits down at the well. The evangelist also notes that “it was about noon”, implying that Jesus—in His sacred humanity—was tired and hot and thirsty. Jesus is like us in all things but sin. His human body needed water just as yours does. That’s why on Good Friday as He was dying on the Cross, Jesus cried out, “I thirst”.[1] Only St. John the Evangelist records Jesus as saying that on the Cross: Matthew, Mark, and Luke do not. For St. John, Jesus saying “I thirst” on the Cross ties into the other teachings that the evangelist records in his Gospel account, especially today’s Gospel Reading.

Jesus, through His human need for water, leads the Samaritan woman to see that she also needs something. Here’s where the double meaning in this passage starts to unfold. Only a few verses at the start of today’s Gospel passage are a discussion about a drink of water for Jesus’ physical thirst. After those first few verses, Jesus shifts the attention away from Himself, and away from His physical need. He shifts the attention towards the Samaritan woman, and toward her spiritual need.

The spiritual thirst that Jesus describes is one that only He can provide water for. The spiritual water that Jesus offers, He calls “living water”. In the physical world, water is not “living” in the way that a plant or animal is. Nonetheless, the spiritual water that flows from Jesus does bear life. This spiritual water flows from Jesus through two of the sacraments that Jesus gave as gifts to His Church: the Sacrament of Baptism, and the Sacrament of Confession. The Sacraments of Baptism and Confession are similar in many ways, all of which can help us appreciate the Good News that Jesus is sharing with the Samaritan woman in today’s Gospel passage. Both Baptism and Confession cause three changes in the person who receives them devoutly.

+ + +

In both the Sacrament of Baptism and the Sacrament of Confession, the person is first of all washed clean of sin. In Baptism, the waters wash away all sin: both Original Sin, and (if the newly baptized is older than the age of reason) any actual sin committed by that individual.

Unfortunately, many people—even many baptized Christians!—only think about Baptism in terms of having sins washed away so that they can get to Heaven. They stop there when they think about Baptism. They think of Baptism only in terms of getting to Heaven. Getting to Heaven, of course, is one part of why we’re baptized: in fact, it’s the ultimate reason; but it’s not the only reason. That reduction of Baptism is what led many in the early Church to delay their own baptism until they were on their deathbed, so that they could be more sure of getting into Heaven!

It’s easy to see how self-focused this kind of thinking is: that I receive God’s grace for me, in order to get me into Heaven. But Jesus did not give His life for us, so that we would make our spiritual life about our self. Instead, Jesus gave His life for us, so that we would give our lives for others. Thinking that Jesus gave His life for us, so that we could make our life about our self is how the world thinks. Jesus is trying to shift our attention to the heavenly way of thinking: so that we would live by Christ’s words that, “whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, [while] whoever loses his life for [Jesus’] sake…will save it”.[2]

Similar to the Sacrament of Baptism, in a sincere, valid Confession, all personal sins—mortal and venial—are washed away. Yet many Catholics reduce the practice of Confession to only one aim: just getting to Heaven, or even just staying out of hell. That’s why many Catholics only go to confession when they’ve committed a mortal sin. But is Confession only for washing away past sins?

+ + +

The second change in the person who receives the Sacrament of Baptism or Confession is a preparation for the future. Not just our future in Heaven, but also our future on earth: however many days, months, and years that might remain for us here on earth. In both Baptism and Confession, God washes something away from our souls: namely, sin. But He also infuses graces into our souls, for the sake of a stronger life on earth.

At the moment of your baptism, when God washed sin away from your soul, He put in your soul the graces of the three supernatural virtues: faith, hope, and charity. God gave these to you not only to help you get to Heaven, but also to change the shape of your earthly life.

Similarly, in Confession, when God washes sin away from your soul, He infuses into your soul the divine gift that the Church calls “sacramental grace”. The graces from Confession give you, in the words of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, “an increase of spiritual strength for the Christian battle”.[3] What does the “Christian battle” involve? Consider just two its demands.

One of the more challenging demands of the “Christian battle” is standing strong in the face of temptation. The Gospel Reading on the First Sunday of Lent described Jesus spending forty days in the desert being tempted. We are like Jesus in facing temptation, but we are much weaker than Jesus Christ. However, the graces from the Sacrament of Confession strengthen us for that “Christian battle” against temptation.

Another challenging demand of the “Christian battle” is forgiving others in a Christ-like manner. When someone has deeply wronged us—especially someone in our family—there’s a temptation to whitewash over it. We’re tempted to just mouth the words “I forgive you” without really meaning it in order to avoid dealing with the problem in a serious way. Often we do this because it’s just too demanding to get into the weeds and really face everything involved in both the sin that caused the problem, and the reconciliation that’s truly needed. So we just punt, and mouth the words “I forgive you.” That’s not how Jesus forgave on the Cross. He put His entire Self into the reconciliation of God and man, and the graces from Confession strengthen us to forgive others in the way that Jesus did on Calvary.

This latter example of the “Christian battle” leads into the third change that Baptism and Confession bring about. This change is also illustrated in today’s Gospel Reading. This passage is not just about the two persons engaged in dialogue, although at first the Samaritan woman might think so, just as you and I might think that our lives as Christians are about our selves. This passage is also about those whom the evangelist mentions at the end of this Gospel Reading: those who “began to believe in [Jesus] because of the word of the woman who testified.”

+ + +

Those words at the end of today’s Gospel passage illustrate the third change that Baptism and Confession bring about within the Christian soul. The third change relates to being part of something larger than your own self. In Baptism, this took place through God the Father’s adoption of you, which joined your life to the lives of your brothers and sisters in Christ. In Confession, you are reconciled with both your God and your neighbor. In the life of the Samaritan woman, this took place through the testimony that she gave to others because of the “living water” that she drank.

So here we can see the problem with “deathbed baptisms”. What if the Samaritan woman in today’s Gospel passage had avoided Jesus all her life, and had waited until the end of her earthly life to drink of that “living water”? How many people around her never would have heard her testimony, and therefore never would have come to Jesus? The longer we wait to allow Jesus’ living waters into our lives, the longer it will be before we can be an instrument of God’s grace, helping others who may have no other way of learning more about Jesus except through our words and actions.

[1] John 19:28; cf. Psalm 69:21.

[2] Mark 8:35.

[3] Catechism of the Catholic Church 1496.

The Second Sunday of Lent [A]

Genesis 12:1-4 + 2 Timothy 1:8-10 + Matthew 17:1-9

St. Anthony’s Catholic Church, Garden Plain, KS

March 1, 2026

The Transfiguration is one of the Luminous Mysteries of the Rosary because it “sheds light” upon who Jesus truly is. Who is Jesus? Part of Jesus’ identity flows from His divinity. This is the more obvious aspect of the scene of the Transfiguration. The glory of Jesus’ divinity shone just for a moment on Mount Tabor before Peter, James and John.

But why was the glory of the Transfiguration only momentary? The answer to that question explains why we hear this Gospel passage during Lent, and also explains the other part of Jesus’ identity, which is His sacred humanity, which He offered in sacrifice on the Cross for our salvation. How these two go together—on the one hand, the everlasting glory of Jesus’ divinity, and on the other, the temporary suffering of Jesus in His humanity—is the heart of today’s Gospel passage.

One of the greatest modern works of Catholic devotional reading is a work titled Divine Intimacy. The author—Father Gabriel—was a 20th century Carmelite friar. In one of his meditations in this work, Father Gabriel notes that the glory of Jesus’ divinity, which shone forth at the Transfiguration, would have shone fully from His birth onwards, had Jesus allowed it to do so. But He did not allow that, just like what He does not allow at the end of today’s Gospel passage after the Transfiguration is over: Jesus charges the three apostles, “Do not tell the vision to anyone until the Son of Man has been raised from the dead.” Throughout His earthly life, Jesus wanted to resemble us sinners as much as possible by appearing “in the likeness of sinful flesh”[1], as Saint Paul put it in his Letter to the Romans.

However, we need to back up. Right before the events of today’s Gospel passage, Jesus had predicted to His apostles His Passion and Death. St. Peter refused to accept this, declaring, “God forbid, Lord! No such thing shall ever happen to you.” Jesus did not take this lying down, but instead replied, “Get behind me, Satan! You are an obstacle to me. You are thinking not as God does, but as human beings do.”[2]

Jesus’ harshness, which He considered justified given the importance of the point, is reinforced by what Jesus says next: “Whoever wishes to come after me must deny himself, take up his cross, and follow me. For whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it.”[3] That leads right into today’s Gospel passage, and the glory of the Transfiguration.

Jesus followed His difficult message—both about His own impending Passion and Death, and the need for His disciples to give up their lives For Him—by revealing one glimpse of His glory to Peter, James, and John. But as heavenly as this glory appeared to Peter, who wanted to pitch tent and rest there, Jesus was making a larger point. Father Gabriel in Divine Intimacy makes two interesting connections between the Transfiguration on Mt. Tabor and the Crucifixion on Mt. Calvary. “Moses and [Elijah] appeared on Thabor on either side of the Savior”[4], just as on Calvary two thieves appeared on either side of Him. And as the thieves on Calvary spoke with Jesus about His death, so St. Luke in his account of the Transfiguration tells us that Moses and Elijah talked with Jesus about His approaching Passion.[5]

So what’s the first point that Jesus is trying to get across to us by His Transfiguration? Jesus “wished to teach His disciples… that it was impossible… to reach the [eternal] glory of the Transfiguration [in Heaven] without passing through suffering.” We might say that these two are intertwined: eternal glory and temporary suffering. “It was the same lesson that [Jesus] would give later to the two disciples at Emmaus [on the day of Jesus’ Resurrection]: ‘Ought not Christ to have suffered these things and so to enter into His glory?’ What has been disfigured by sin cannot regain its original supernatural beauty except by way of purifying suffering.”[6]

Today’s Gospel’s first point is that we cannot avoid suffering if we’re going to follow Jesus. The second point is about how the glory of the Transfiguration is part of our ordinary Christian lives in the 21st century. This point has to do with what theology calls “spiritual consolations”. You could describe spiritual consolations as small gifts of grace that God gives whenever He chooses. Spiritual consolations are above and beyond the graces we receive through the sacraments and private prayer. These spiritual consolations may take many different forms, and God gives them for various reasons, but He always gives them as pure gifts. They’re sort of like a husband giving his wife roses, not on her birthday, and not on their anniversary, but on a random Tuesday, “just because”.

Father Gabriel in his work Divine Intimacy explains that “[s]piritual consolations are never an end in themselves, and we should neither desire them nor try to retain them for our own satisfaction. … To Peter, who wanted to stay on Thabor in the sweet vision of the transfigured Jesus, God Himself replied by inviting [Peter] to listen to and follow the teachings of His beloved Son.”[7] And what had that Son just taught? That Son had just taught Peter and all His disciples that He—Jesus Himself—must suffer and die, and that each of them, and each of us, must deny himself, take up his own cross, and follow Jesus to Calvary. That’s the only way to the glory of Heaven.

Father Gabriel continues: “God does not console us for our entertainment, but rather for our encouragement, for our strengthening, for the increase of our generosity in suffering for love of Him.” Then Father Gabriel turns back to today’s Gospel passage.

“The vision [of the Transfiguration] disappeared; the apostles raised their eyes and saw nothing [except] Jesus alone, and with ‘Jesus alone’, they came down from the mountain. This is what we must always seek and it must be sufficient for us: Jesus alone… Everything else—consolations, helps, friendships (even spiritual ones), … esteem, encouragement…—may be good to the extent that God permits us to enjoy them. He very often makes use of them to encourage us in our weakness; but if, through certain circumstances, His divine Hand takes all these things away, we should not be upset or disturbed.

“It is precisely at such times that we can prove to God more than ever… that He is our All and that He alone suffices. On these occasions the loving soul finds itself in a position to give God one of the finest proofs of its love: to be faithful to Him, to trust in Him, and to persevere in its resolution to give all…. The soul may be in darkness, that is, subject to misunderstanding, bitterness, material and spiritual solitude combined with interior desolation. [When you reach this point, the] time has come to repeat, ‘Jesus alone’, to come down from Thabor with Him, and to follow Him with the Apostles even to Calvary ….”[8]

[1] Romans 8:3.

[2] Matthew 16:22,23.

[3] Matthew 16:24-25.

[4] Divine Intimacy, 309.

[5] Luke 9:30-31.

[6] Divine Intimacy, 310, quoting Luke 24:26.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid., 310-311.

CLICK ON THE COVER BELOW FOR MORE ABOUT DIVINE INTIMACY.

Please note that Father Gabriel lived before the Second Vatican Council. His meditations are arranged according to the liturgical calendar used during his life.

The First Sunday of Lent [A]

Genesis 2:7-9; 3:1-7 + Romans 5:12,17-19 + Matthew 4:1-11

St. Anthony’s Catholic Church, Garden Plain, KS

February 22, 2026

The word “sacred” is not used much anymore. As Catholics, we know instinctively that certain persons, places, and things are sacred, but what does that mean? Being clear on the meaning of the word “sacred” will help us appreciate today’s Gospel Reading.

Consider some examples of sacred objects. What would you think if you visited a neighbor, and noticed that he propped his back screen door open with a bible? When you ask your neighbor why he’s doing that, he replies that that particular bible is just the right size to fit under the door, to hold it in place. None of the other books in his house would do the trick.

Then the next day you go over to your cousin’s house for supper. She tells you that you’re having chicken soup for dinner. The smell is delicious. But when it’s time to start serving, your cousin takes an old chalice, and uses it to ladle the soup. When you ask why she’s doing that, she says that her old ladle broke, and she had this chalice laying around because a deceased uncle was a priest and bequeathed it to her.

In both cases, you would likely be shocked. But when you tell your neighbor and cousin that they were doing something wrong, they ask you “Why? Why is it wrong?” How would you answer them?

The answer would boil down to the meaning of the word “sacred”. The word “sacred” means “set apart for God”: set apart from others of the same for God.

Think back to your neighbor using his bible to prop open his door. He said that the bible is “just the right size” for keeping his door open. He thinks the bible is fitting for that purpose. But a bible is sacred. It is a book bearing the written Word of God, in order to be read (whether liturgically or devotionally). This book is not to be used as a doorstop, or a paperweight, or any other purpose, even if it seems well suited to other purposes. Any other use is an act of sacrilege. The sin of sacrilege is using something sacred for a purpose other than its divine purpose.

What about your cousin using her uncle’s chalice to ladle chicken soup? She might argue that the chalice serves well as a ladle. But a chalice is sacred. Each chalice, before it’s used for the first time, is consecrated by means of prayer. It’s consecrated for the purpose of bearing the wine that is changed into the Precious Blood of Jesus. The chalice must not be used as a ladle, or as a cup for drinking beverages, or for any other purpose. Any other use is sacrilege.

+ + +

Now this might seem obvious to anyone brought up Catholic. But we don’t live in a world today that understands the meaning of the word “sacred”. Our day and age doesn’t get the notion of “consecration”. The world that surrounds us does not believe that there is anything called “sacrilege”. The motto of the modern world is “anything goes”. Or to use a more technical word, the modern world believes that every thing, and every person in this world is nothing more than “secular”. That is to say: the only meaning of any thing or any person is the meaning that it has in this world. There is no world beyond this world that sheds further meaning on any thing or any person.

The challenge for you as a Christian comes from the fact that it’s not just a printed bible and a consecrated chalice that are sacred. There’s something else in your life that’s sacred, which in fact you carry with you everywhere you go, including to the store, the workplace, on vacation, and so on. That is your very self.

Your very self—your body, your mind, and your soul, all united as the person who is you—is sacred. At the moment of your baptism, you as a person were consecrated to God and for God. Of course, that begs a question: for what purpose were you “set aside” as sacred? If a bible’s purpose is to let God’s Word be revealed, and if a chalice’s purpose is to let God’s Precious Blood be consumed, then what is the purpose for which you yourself were consecrated at your baptism? Or course, there are different vocations within the Church—married persons, priests, and consecrated religious—but God gives every Christian the same overarching goal. The different Christian vocations all reach for the same end.

The end for which you were consecrated as a Christian person is to love: to love your God and to love your neighbor, and—what’s more—to do both as Jesus Christ loves.

God calls you to love in this way not only in church on the weekend, but also in the midst of the world every day. This is a difference between a sacred chalice and you as a baptized Christian. The chalice is used only within the sanctuary of the church, while you can live out the Gospel anywhere in the world. Every day, and in every place, Jesus calls you—as He proclaimed in His Sermon on the Mount—to be “the salt of the earth” and “the light of the world” [Matthew 5:13,14].

Today’s First Reading is about the corruption of God’s plan for the human family to share fully in God’s love. But the Gospel Reading is about Jesus starting to set things back on course. In this passage from Matthew, Jesus helps us appreciate the challenge that each of us received on the day of baptism: the vocation to be loving in all of our thoughts, words, and actions towards both God and neighbor, as Jesus loves.

More specifically, today’s Gospel passage is about one specific roadblock to loving in a Christ-like manner. This roadblock is called temptation. Today’s Gospel passage is about the different ways in which we’re tempted not to be loving, or rather, to love in ways that are not Christ-like.

+ + +

Consider, then, the insights of one of the Church’s spiritual masters: St. Francis de Sales, who was the bishop of Geneva (in what today is Switzerland) in the early 1600’s. In commenting upon today’s Gospel passage, St. Francis de Sales points out that “many prefer the end of today’s Gospel to its beginning.” In other words, people are happy to be with Jesus when He’s surrounded by angels who bring Him comfort and consolation. But are we willing to be with Jesus in the trials of the desert? St. Francis explains that we will never be invited to His heavenly “banquet… if we [do not share in] His labors and sufferings”.[1]

St. Francis de Sales continues by pointing out that in the here and now, we should “busy ourselves in steadfast resistance to the frontal attacks of our [moral and spiritual] enemies. For whether we desire it or not[,] we shall be tempted.”[2]

St. Francis de Sales forcefully denies the common misconception that the more dedicated we are to God, the less we will experience temptation. He explains that just the opposite is to be expected: “it is an infallible truth that no one is exempt from temptation [once] he has truly resolved to serve God.”[3]

This is clearly illustrated by today’s Gospel Reading. The divine Son of God was tempted by the devil just before the start of His three years of public ministry. The devil sought out Jesus at this point because Jesus was ready to start His earthly mission, putting behind Him thirty years of living quietly with His family in the home at Nazareth.

So if you take up this season of Lent with strong resolve, expect pushback from those who do not want you to become more like God. With this expectation in mind, there are two more points from St. Francis de Sales about what it means for a Christian to experience temptation.

First, St. Francis points out “that although no one can be exempt from temptation, still[,] no one should seek it[,] or go of his own accord to the place where it may be found”[4]: that place is called “the near occasion of sin”.

Second, given the fact that every Christian will face temptation, it’s “a very necessary practice to prepare our soul for temptation.” This is one of the most important works of the Christian spiritual life: to prepare oneself to battle against temptations. St. Francis de Sales puts it like this: “we ought to … provide ourselves with the weapons necessary to fight valiantly in order to carry off the victory, since the crown is only for the combatants and conquerors.”[5]

In saying this, he’s echoing the language of Saint Paul the Apostle, who frequently throughout his New Testament letters describes the Christian virtues using metaphors of military gear. It’s only modern thinkers who falsely claim that military language has no place in the Christian life. Modern thinkers take for granted that we enjoy the blessings of modern life only through the blood, sweat and tears of those who went before us. As the bumper sticker puts it, “freedom isn’t free”. Freedom comes at a price, even if you are not the one who had to pay it.

The same is true in the Christian spiritual life. Jesus Christ paid the ultimate price to open the gates of Heaven for you. Only Jesus Christ—as the only-begotten divine Son of the Father—could accomplish that. Yet every Christian must follow Him there on the same Way. Every Christian must reject the temptation to wander off the Way of the Cross that leads to Heaven. Certainly, following Christ faithful along this Way is often a battle.

That truth is reflected in the opening prayer of Holy Mass on Ash Wednesday. Listen again to the words of this prayer, and ask Jesus for the grace to fight temptation, in order to be faithful to your sacred call to be loving as Jesus is loving: “Grant, O Lord, that we may begin with holy fasting / this campaign of Christian service, / so that, as we take up battle against spiritual evils, / we may be armed with weapons of self-restraint.” Amen.

[1] St. Francis de Sales, The Sermons of St. Francis de Sales for Lent (Rockford, Ill.: Tan Books, 1987), 31.

[2] Ibid., 32.

[3] Ibid., 15.

[4] Ibid., 15.

[5] Ibid., 17.

The Sixth Sunday in Ordinary Time [A]

Sirach 15:15-20 + 1 Corinthians 2:6-10 + Matthew 5:17-37 [or Matthew 5:20-22a,27-28,33-34a,37]

St. Anthony’s Catholic Church, Garden Plain, KS

February 15, 2026

Three years ago, I made a pilgrimage to Portugal, Spain, and France. Both bookends of the pilgrimage were in honor of Our Blessed Mother, starting at Fatima in Portugal, and ending two weeks later at Lourdes in France. In between, the bulk of the pilgrimage was spent in Spain.

I visited many different places in Spain connected to the lives of two 16th century saints. St. Teresa of Jesus and St. John of the Cross lived at a time of great chaos. Part of this chaos was caused by corruption within the Catholic Church.

St. Teresa of Jesus decided to confront the corruption within the Church differently than the Protestant leaders whose efforts started during the 16th century. Instead of leading Christians out of the Church, she decided to remain within the Church, and to change the Church from within. St. Teresa belonged to the Carmelite religious order, which had grown lax since their foundation in the 12th century. So she started a new branch of the Carmelites called the Discalced Carmelites. (The word “discalced” means “barefoot”, because the Discalced Carmelites, as part of their vow of poverty, went without shoes.)

+ + +

Now, why do some religious orders like the Carmelites grow lax and weak over time, or even corrupt? It’s much the same reason that a relationship grows weak. You cannot take relationships for granted. You have to dedicate time and effort to relationships. Husbands need to take their wives out on “date nights”. Parents and grandparents “make memories” with their children and grandchildren.

Something similar is also true of the spiritual life. This is part of the battle that St. Teresa of Jesus faced in her reform of the Carmelite order. You cannot take your soul’s health for granted. Unless you tend to it, like a gardener or a farmer, weeds will grow, disease will set in, and death will follow. If not tended to in this world, that death will last forever in the next. What’s true of an individual soul is just as true for a religious community of monks or nuns: if growth is not fostered, the spiritual life becomes lax, and decay sets in.

That brings us to the conflict in today’s Gospel passage. This conflict reflects the conflict that St. Teresa of Jesus and St. John of the Cross faced in 16th century Spain. This conflict reflects the struggle that’s present in every Christian’s spiritual life, including your own.

+ + +

Today’s Gospel passage is from the middle of Matthew 5. Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount is found in Chapters 5-7 of Matthew. Today is the third Sunday in a row on which the Gospel Reading comes from Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount. Since Lent starts this week, we won’t hear the rest of the Sermon on the Mount over the next few Sundays. However, at home you can place a bookmark in your bible at the start of Matthew 5. Slowly read and meditate upon Matthew Chapters 5, 6 & 7 over the weeks from now until Easter Sunday.

Now if tackling the entire Sermon on the Mount seems daunting, just take Matthew 5. Even though Matthew 5 is just one-third of the Sermon on the Mount, the chapter is rather self-contained. Matthew 5 starts with the Beatitudes, and ends with Jesus saying, “So be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect” [Mt 5:48]. So at the start of Matthew 5, when He starts the Sermon on the Mount, the Beatitudes are the roadmap that Jesus hands to us, so that we can follow Him on a spiritual journey. At the end of Matthew 5, Jesus reveals the goal of our spiritual journey: to “be perfect, as your heavenly Father is perfect”.

In between, Jesus describes several conflicts that we’re likely to face on this spiritual journey: road bumps, you might say, on the path to becoming perfect as our heavenly Father is perfect. The spiritual conflicts that Jesus describes in Matthew 5 are similar to the conflicts that St. Teresa of Jesus and St. John of the Cross faced in their efforts to reform the Carmelite order. Consider what happened to St. John of the Cross in the year 1577.

John was kidnapped by members of the older Carmlite order. They imprisoned him for eight months in a cell that measured ten feet by six feet, and they lashed him once a week. In the midst of this, he was also bribed. The bribes were unsuccessful, John eventually escaped, and the reform efforts of St. John and St. Teresa continued successfully.

+ + +

So consider the conflict in today’s Gospel passage.

Jesus does not describe a conflict between the Jewish Law and His Gospel. In fact, He declares, “Do not think that I have come to abolish the law or the prophets. I have come not to abolish but to fulfill.”

The conflict is between—on the one hand—the righteousness of the scribes and the Pharisees, and—on the other hand—the righteousness that Jesus offers.

The righteousness of the scribes and the Pharisees was limited to the literal meaning of the 613 laws of the Jewish Torah. Jesus demanded more. Jesus demands that if you’re going to follow Him, you have to go to the heart of God’s laws. Ask where evil starts in the human heart. Don’t just consider where it ends. Every man who murders a man commits the murder twice: first in his heart, by way of desire, and then a second time in fact. The Scribes and Pharisees thought they could be righteous if they only murdered a man once, as long as it was only in their heart, because in their reading of God’s Law, God did not make demands of their hearts.

Jesus is making a demand of you: “unless your righteousness surpasses that of the scribes and Pharisees, you will not enter the kingdom of heaven.” As you start the Season of Lent this week, allow God’s demands to reach into your heart, and touch every desire that you hold there. Offer to Christ every desire in your heart that’s contrary to His love, and ask Him in exchange to give you the Love that can re-shape and re-form your heart to be like the Sacred Heart of Jesus.

The Fourth Sunday in Ordinary Time [A]

Zephaniah 2:3;3:12-13 + 1 Corinthians 1:26-31 + Matthew 5:1-12

St. Anthony’s Catholic Church, Garden Plain, KS

February 1, 2026

The Bible is not a single book. The Bible is a library. Just as a library has many different types of books in it, so also the Bible. When you visit a library, you find different sections in the library, and each section has different books. If you visit a library, and visit four different sections, and take from different shelves a cookbook, a collection of poems, a presidential biography, and a science fiction novel, you don’t read those four books in the same way. For example, if you open a cookbook expecting it to read like a science fiction novel, you’re going to end up with a very strange supper.

The Bible is the same way, and this variety among the books of the Bible is important to remember during Holy Mass. As you know, the first chief part of the Mass focuses upon passages from the Bible. But when we listen to them, if we don’t understand the differences among the Old Testament Prophets, the New Testament letters of the Apostles, and the four Gospel accounts, we’re not going to get the most out of the Scripture readings.

What’s more, when it comes to the four accounts of the Gospel—written by Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John—we need to recognize the many differences among these four books of the Bible. One way to understand these many differences is to think of your own life. Let’s say that I myself wanted to commission a biography of your life. I hire four different journalists to write four different biographies of your life. But each of these four journalists interviews a different person. One journalist interviews your spouse. Another interviews one of your bosses from the jobs you’ve had over the years. Another interviews one of your sisters, and the last journalist interviews one of your high school friends. Do you think that those four biographies are going to say the same thing? Or are these four biographies going to illustrate different aspects of your life? In fact, they are going to illustrate four different aspects of your life. In a similar manner, each of the four Gospel accounts illustrates Jesus’ life, death, and Resurrection from different vantage points because the four different authors had four different sources.

I mention all this because we are early in the Season of Ordinary Time, and have just heard today one of the most important passages of the Bible. Before reflecting specifically on this passage—from Matthew 5—we need some context.

Lent starts early this year, on February 18. So including today, we only have three Sundays in Ordinary Time before Lent begins. On these three Sundays, the Gospel passage comes from Matthew Chapter 5. This chapter is the first of three chapters that give us Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount. If you’d like a recommendation for spiritual reading during these next three weeks before Lent begins, I’d encourage you to read the Sermon on the Mount from the Gospel according to St. Matthew.

+ + +

Today’s Gospel passage is the first twelve verses of Matthew Chapter 5: the very beginning of the Sermon on the Mount. In our own day, preachers often begin a sermon with a story or a joke. Jesus decided to begin His Sermon on the Mount with the Beatitudes.

However, before he starts giving us Jesus’ sermon, St. Matthew the Evangelist mentions a few interesting details about Jesus. The evangelist mentions that when “Jesus saw the crowds, He went up the mountain, and after He had sat down, His disciples came to Him.” Consider just two points here: that Jesus went up the mountain, and that He sat down there.

Why did Jesus have to go up a mountain in order to preach a sermon? Obviously, He did not have to. Jesus preached many sermons during the three years of His public ministry, and most of them were preached in all sorts of settings. But in St. Matthew’s account of the Gospel, the Sermon on the Mount is Jesus’ first sermon, so Jesus is teaching us here not only by His words, but also by the setting that He chose, and by the choice to sit down.

So why did Jesus choose a mountain to be the site of His first sermon? St. Matthew clarifies this throughout the course of his Gospel account. Through the words and works of Jesus that St. Matthew includes, and in the way he structures his Gospel account, St. Matthew portrays Jesus as a “New Moses”. One reason St. Matthew does this is that unlike many other New Testament writings, Matthew’s Gospel account was written for converts from Judaism.

So here you need to notice another difference among the four accounts of the Gospel. The four accounts of the Gospel differ because the four evangelists were writing for four difference audiences. Imagine again the biography of your own life. Instead of myself commissioning four different journalists to write four biographies, imagine that four different persons commission four biographies of your life. Furthermore, imagine—and granted, this will take quite a bit of imagination—that the four persons who commission these four biographies are four very different persons. The first of those who commissions a biography of you is a farmer from Kingman County. The second is a businessman from New York City. The third is a tribesman from the Amazon of South America. And the fourth—again, use your imagination—is an astronaut from the 26th century who lives in a colony on Saturn.

When those four different biographies of your life are written for those four very different people who commissioned the biographies, the authors are going to have to write differently. The author writing for the tribesman from the Amazon is going to have to explain details and circumstances about your life that the farmer in Kingman County is not going to need to have explained. The audiences of the books shape the way that the same story is told. It’s similar with the four accounts of the Gospel.

Matthew’s Gospel account was written for converts from Judaism. This is why Matthew “refers to Jewish customs and institutions without explanation” of their backgrounds, because the original Jewish audience of Matthew’s Gospel account would already have known those backgrounds. That’s also why St. Matthew “works nearly two hundred references to the Jewish Scriptures into his narrative”.[1] That’s also why St. Matthew draws parallels between Jesus and Moses.

Moses was, for the Jewish people, the greatest Old Testament Prophet. His life as a prophet including working signs and wonders during the Exodus. But during that Exodus came the most important event of Moses’ life as a prophet. During the course of their Exodus from Egypt to the Promised Land, God’s People stopped at Mount Sinai. There, while the rest of God’s People remained below, Moses alone ascended Mount Sinai to receive from God His Ten Commandments. Moses then had to descend the mountain to give to God’s People this Law. This Law was the means by which His People could—we might say today—“keep right” with God. That key truth about Moses is reflected in how St. Matthew records his account of the Gospel, portraying Jesus as a “New Moses”. Jesus is like Moses in many ways, but also fulfills and completes the ministry of Moses.

In today’s Gospel Reading, it’s not only Jesus who ascends the mountain. Jesus draws His disciples up with Him. And it’s not a voice from the heavens that speaks there to a prophet. Instead, the New Moses—God in the Flesh—speaks to His people face to face. And Jesus gives to us, His people, not ten commandments, but nine beatitudes.

+ + +

Jesus put the Beatitudes at the start of the Sermon on the Mount in order to put the most important lesson first. Likewise, the first of the nine Beatitudes is the key to understanding and living out all nine. So we ought to consider the first of the nine beatitudes as being the first for a reason.

“‘Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the Kingdom of Heaven.’” St. Augustine preaches about this first—this key—beatitude by asking what “poor in spirit” means. He answers that it means “[b]eing poor in wishes, not in means. One who is poor in spirit, you see, is humble; and God hears the groans of the humble, and doesn’t despise their prayers. That’s why the Lord begins His sermon with humility, that is to say with poverty. You can find someone who’s religious, with plenty of this world’s goods, and not [because of that] puffed up and proud. And you can find someone in need, who has nothing, and won’t settle for anything. … the [former] is poor in spirit, because humble, while [the latter] is indeed poor, but not in spirit.”[2]

The Lord Jesus has given us what we need to reach Heaven. He has given us life; grace to strengthen us for the journey; and the roadmap in these nine beatitudes. The first, upon which all the others rest, is humility: poverty of spirit. Ask the Holy Spirit to help you to make a concrete resolution regarding the practice of humility, maybe by serving those in need through either the Corporal or Spiritual Works of Mercy, or by giving up something that you have and do not need.

[1] “Introduction to the Gospel according to Saint Matthew”, in The Ignatius Catholic Study Bible (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2010), 4.

[2] St. Augustine of Hippo, Sermon 53A, in The Works of Saint Augustine, Part III, Vol. III, 78.

The Third Sunday in Ordinary Time [A]

Isaiah 8:23-9:3 + 1 Corinthians 1:10-13,17 + Matthew 4:12-23

St. Anthony’s Catholic Church, Garden Plain, KS

January 25, 2026

This Sunday’s Gospel Reading is a good reminder to pray often for one member of our parish who—God willing—will be ordained to the priesthood at the end of May. Deacon Peter Bergkamp is nearing the finish line of the long marathon called “seminary”. Of course, in the spiritual life, where one spiritual marathon ends, another begins.

It’s not an easy road to enter the seminary. Before being admitted, the young man has to take intelligence tests, a psychological examination, and a physical. But the most grueling requirement is saved for last: the candidate has to play a round of golf with the Bishop, and shoot under 80.

There are many things about a young man entering the seminary that are misunderstood. One important point that many people are not clear on is why exactly a young man enters the seminary. He does not enter the seminary because he’s decided to be a priest. A young man enters the seminary to find out if he’s being called to the priesthood.

To put this differently: the Lord calls out to every young man, “Come after me….” What differs from one young man to another is the phrase that follows “Come after me….” To some young men, the Lord says, “Come after me, and I will give you the grace needed to be a strong and virtuous husband and father.” To other young men, Jesus says those words by which we hear him calling Simon and Andrew: “Come after me, and I will make you fishers of men.” Through a seminarian’s prayers while in the seminary, the Lord clarifies just which call the Lord has made to him.

“Fishers of men”. This is a metaphor, of course: one that Simon and Andrew readily understood, since their livelihood was being fishermen. Regardless of the kind of life which they had chosen for themselves, Jesus called them to a very different way of life. They had no idea what to expect, and if Jesus had tried to explain what following Him would mean, they still would have been largely in the dark. That’s why following Jesus demands the virtue of faith. Following Jesus is not for those who insist on controlling everything, or knowing exactly what’s coming down the pike.

The fact is that Jesus can call men from any sort of livelihood, at any age in their lives, to serve His Church as priests. For the last four years of my formation in the seminary, Bishop Gerber sent me and another young man named Sam Pinkerton to Mundelein Seminary in Chicago, which at the time was the largest seminary in the United States. It served forty-five dioceses throughout the world, educating men from the countries of Uganda, Zaire, Colombia, Poland, China, Vietnam in addition to U.S. dioceses from Paterson, New Jersey to El Paso, Texas, and of course a large contingent of native Chicagoans, who are a breed all their own.

Among the 150+ men with whom I studied at Mundelein, I can guarantee you that no two of us had traveled along the same path to get to the seminary. I can also guarantee that the Lord did not use exactly the same words to call any of us, to help us understand the need we had to enter the seminary.

Before entering the seminary, I had spent only one year at Kansas State. Many young men enter the seminary the summer after graduating from high school. But some men enter the seminary after graduating from college and starting careers. At the seminary I attended in Chicago, one seminarian had graduated from law school and practiced law before entering the seminary. Another seminarian had finished medical school and practiced medicine before entering the seminary. No two young men have the same path to the priesthood.

It’s also important to realize that God calls young men of many different temperaments and with many different outlooks on life to enter the seminary. Some years ago there was a book published that illustrated this truth. It offers portraits of about a dozen different priests, one of whom—Father Ned Blick—is a priest of our diocese.

Father Ned’s words in this book ring very true. He states:

“Since I have been ordained, I have been surprised, no, astonished, by the effect on people of things that require such a small effort on my part. … I had no idea such small things would be so much appreciated. Why that happens to priests is interesting. It may be because we confront the spiritual dimensions of people, while most other professions do not. People have deep spiritual needs. When they see them met, however inadequately, they respond.”

To me the key of this quote is Father Ned speaking about the spiritual nature of man: a dimension of human nature that’s often ignored. Again, Father Ned states: “we confront the spiritual dimensions of people, while most other professions do not. People have deep spiritual needs. When they see them met, however inadequately, they respond.”

This spiritual side to human nature is where the great gift of the priesthood rests. We need to pray for vocations to the priesthood. But we also need to encourage young men to offer themselves to the spiritual nature of man that gives our lives their final and ultimate meaning.

The Second Sunday in Ordinary Time [A]

Isaiah 49:3,5-6 + 1 Corinthians 1:1-3 + John 1:29-34

St. Anthony’s Catholic Church, Garden Plain, KS

January 18, 2026

In Abilene, Kansas, across the street from the Eisenhower presidential library, and the resting places of Dwight and Mamie Eisenhower, is a Catholic church by the name of St. Andrew’s. In that church, on December 17, 1967, I received the Sacrament of Baptism. Hopefully you, also, know the date of your baptism, and honor that day each year with prayers of thanksgiving to God.

That’s important to do because on the day you were baptized, God made promises to you, and you made promises to God (or your parents did on your behalf). These two-way promises founded a relationship where God is your Lord, and you are His servant. Of course, whenever someone serves the Lord, he does something specific for him. So we hear several examples of this servant—Lord relationship in today’s Scriptures. Each is a model for us, and the last is also something more.

+ + +

First is the Old Testament prophet Isaiah. What specific job did God call Isaiah to do for Him? God called Isaiah to serve Him as His prophet. We hear this in the First Reading. “The Lord said to [Isaiah]: ‘You are my servant. … I will make you a light to the nations, that my salvation may reach to the ends of the earth.’” Among all the Old Testament prophets, Isaiah had a unique place. His call was to proclaim the coming of a Messiah who offers a loving mercy that knows no bounds and that would “reach to the ends of the earth”, meaning even to the Gentiles. Although none of us has been called to be a prophet like Isaiah, his vocation mirrors our own vocation as a baptized Christian: namely, to love others with a mercy that knows no bounds.

+ + +

Second is the New Testament apostle Paul. What specific job did God call Paul to do for Him? God called Saul (renaming him Paul) to serve Him as His apostle. Today’s Second Reading is simply the first three verses of a letter written by Saint Paul: it’s not the longest of his letters, but it’s one of the more profound. Paul’s self-introduction focuses upon his calling as an “apostle”, which literally means “one who is sent”. He describes himself this way: “Paul, called to be an apostle of Christ Jesus by the will of God”.

Paul was sent “by the will of God” to spread the Messiah’s Gospel to the Gentiles, the very people that Isaiah had served by preparing them for the Messiah. Although none of us has been called to be an apostle like Paul, his vocation mirrors our own vocation as a baptized Christian: namely, serving as “one who is sent”, or in other words, serving as one who takes his cues from God.

+ + +

Now that Messiah whose coming Isaiah foretold, and whom Paul was sent forth to preach about, is of course Jesus. In fact, Jesus—like Isaiah and Paul—was called by God to serve. Yet Jesus is not only an example for us, as are Isaiah and Paul. Jesus’ call is unique. He’s an example, and something more.

Jesus was called by God the Father to serve as the Savior of mankind. We hear about this call within today’s Gospel Reading. This call connects to today’s Responsorial Psalm, and especially its refrain. That refrain can help you rest in God’s will for your daily life, instead of wrestling against it.

“Here am I, Lord; I come to do your will.” That’s a good verse to memorize, and to pray often. You can recite it slowly as your make a Holy Hour before the Blessed Sacrament. You can recite it slowly as you drive to work. You can recite it (very) slowly at 2:00 am on Saturday morning as you wait for your teenager to get home.

“Here am I, Lord; I come to do your will.” Although the word “I” appears twice in this single verse, it’s not the focus of the verse. The focus is God’s Providential Will and an individual’s submission to it: that is, an individual’s willingness to be God’s servant. Unfortunately, many of us when we pray actually speak to God as if He is our servant: in effect saying, “Here I am, Lord; now come and do my will.”

+ + +

Throughout the first several weeks of Ordinary Time, our Scriptures at Holy Mass help us set our own lives within the grander scheme of things. That grander scheme is called “Divine Providence”. One way to describe Divine Providence is to say that it’s what God chooses to do, when He does it, and why He does it.

Although it might sound odd, one of the chief ways that Christians experience God’s Providential Will is unanswered prayers. In fact, these are often God’s gifts to us, whether we acknowledge them as such or not. Unfortunately, some Christians stop following Jesus because their prayers aren’t answered as they want. But silence on God’s part can be His way of demanding patience and perseverance. This silence clarifies what’s important to God for the unfolding of His Providential Will.

Nonetheless, whether in accepting God’s silence for the gift that it is, or in moving forward to carry out His Will, it’s important to recognize a distinction. We are not only to imitate Jesus in His example of doing His Father’s Will. As Christians, we are meant for something even greater: we are meant to live in Christ.

We are not meant to live “in Isaiah” or “in Paul”, as much as we ought to follow their respective examples. But each of us is meant to live “in Christ”. This is not something that the Christian can accomplish through human effort or good works. Only God can accomplish this. His chief means for doing so are the Sacraments and grace given through personal prayer. For our part, we work at disposing ourselves to God’s graces and charisms. These gifts from God allow Christ to live within us, and allow Christ to say through us: “Here am I, Lord; I come to do your will.”

The Baptism of the Lord [A]

Isaiah 42:1-4,6-7 + Acts 10:34-38 + Matthew 3:13-17

St. Anthony’s Catholic Church, Garden Plain, KS

January 11, 2026

“Childhood” is a key theme of Christmas. First, we focus on the Christ Child. But like everything in Jesus’ earthly life: Christ’s childhood is for us. Christmas also focuses upon you and me being called to adoption as God’s very own children. In St. John’s first New Testament letter, he writes about this divine adoption, proclaiming: “See what love the Father has bestowed on us that we may be called the children of God. And so we are. … Beloved, we are God’s children now” [1 John 3:1-2].

That’s not just a mystery. It’s also a profound paradox. It’s hard enough to imagine how a tiny baby could be the All-Powerful Creator of the universe. But it’s even harder to imagine how a sinner such as you or me could become, not just a saint, but a very child of God the Father! But “so we are”, St. John proclaims: “we are God’s children now”.

The Sacrament of Baptism is how we become God’s children. But our own baptism was made possible by the Baptism of the Lord Jesus in the Jordan River. This is the sacred mystery that the Church celebrates on last day of Christmas. Today we reflect on the mystery of Jesus’ baptism in order to understand your and my baptism.

So what difference does being baptized make to the life of a Christian in this world? St. Paul gives an answer in his New Testament Letter to the Romans. He explains to the first Christians in Rome that “we were buried… with [Jesus] by baptism into death, so that… we too might walk in newness of life” [Romans 6:4].

What is St. Paul saying here about your daily life as a Christian? What does it mean to “walk in newness of life”, and how does that connect to being “buried… with [Jesus] by baptism into death”?

Imagine someone baptized as an adult. What is different about the way that that adult walked through life before baptism, over and against the way that he walks through life after baptism? The answer is that after baptism, the Christian walks through life by means of death. But what exactly does that mean, that by virtue of your baptism, you are meant to walk through life by means of death?

One way of explaining it is that your life is not about your self. Your life as a Christian is about God first, your neighbor second, and your self third. The living of the Christian life means loving God and loving your neighbor, and living for God and living for your neighbor. This is instead of rooting your life in your love of your self, and living for the good of your self and your comfort: in a word, the Christian life is the process of becoming “self-less”.

To live a “self-less” life means to live your daily life through the strength of your baptism, by means of death. If this seems abstract, the saints of our own day and time give us clear examples. Take St. Teresa of Calcutta. If you’ve never watched a documentary of her life in Calcutta, watch one on YouTube. Watch Mother Teresa in the slums of Calcutta, loving God at the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass and in Adoration of the Blessed Sacrament early each morning. Then, during the rest of the day, through the strength she received in Adoration and Holy Mass, she loved the “poorest of the poor”, as she called her neighbors. She tended to their needs by carrying out the corporal and spiritual works of mercy.

Saints like Mother Teresa are easy to admire, but how does the average Christian go about opening her or his life to God’s grace more fully? One simple question that helps is to ask yourself whether you can name from memory the seven corporal works of mercy and the seven spiritual works of mercy. If not, find them listed in the Catechism, write them down on a sheet of paper, and pray over this list of fourteen simple actions: two columns of seven works of mercy.

So here are three action items for this coming week. Choose just one of these, unless you feel really enthusiastic about doing all three. (1) Find out, if you don’t already know, the date of your baptism, and put a note in your 2026 calendar to observe your baptismal anniversary with prayer and maybe even going to Mass. (2) Watch a documentary about St. Teresa of Calcutta. (3) Write out longhand the seven corporal works of mercy and the seven spiritual works of mercy, and choose one out of those fourteen to focus on during the rest of this month. Pick a different work of mercy for each month.

Albert Einstein is supposed to have stated that genius equals 1% inspiration and 99% perspiration. Something similar is true of holiness. In the case of holiness, God the Holy Spirit offers us the inspiration. Your work after accepting that grace is the 99% of perspiration through acts of love for God, and acts of love for your neighbor, dying to your self, so as to live completely within the Mystical Body of Christ.