The Eleventh Sunday in Ordinary Time [C]

II Samuel 12:7-10,13 + Galatians 2:16, 19-21 + Luke 7:36—8:3

Summer is a time for activity and travel. In the midst of so much of nature—the great outdoors—that we get to enjoy during these months, it’s easy to overlook the great “indoors”: not the inside of our homes and campers, but rather, the inside of our souls. In the midst of so much natural beauty, we need to spend time admiring and cultivating the supernatural beauty of the Christian spiritual life. A large part of this beauty emerges through Christian prayer.

What is prayer? St. Thérèse the Little Flower simply said this: “For me, prayer is a surge of the heart; it is a simple look turned toward Heaven, it is a cry of recognition and of love, embracing both trial and joy.”[1] Despite her simplicity, the Little Flower packed a lot of truth into that single description. But consider just one part of her description of prayer: that part in which she says, “For me, prayer is a surge of the heart”.

Prayer is not something abstract, but something personal. It’s not something that the Little Flower has heard about, like an exotic animal that lives only in some far-away country in Asia. This is something she’s experienced—not only first-hand—but within her. That’s why she uses the metaphor of the “heart” in describing prayer.

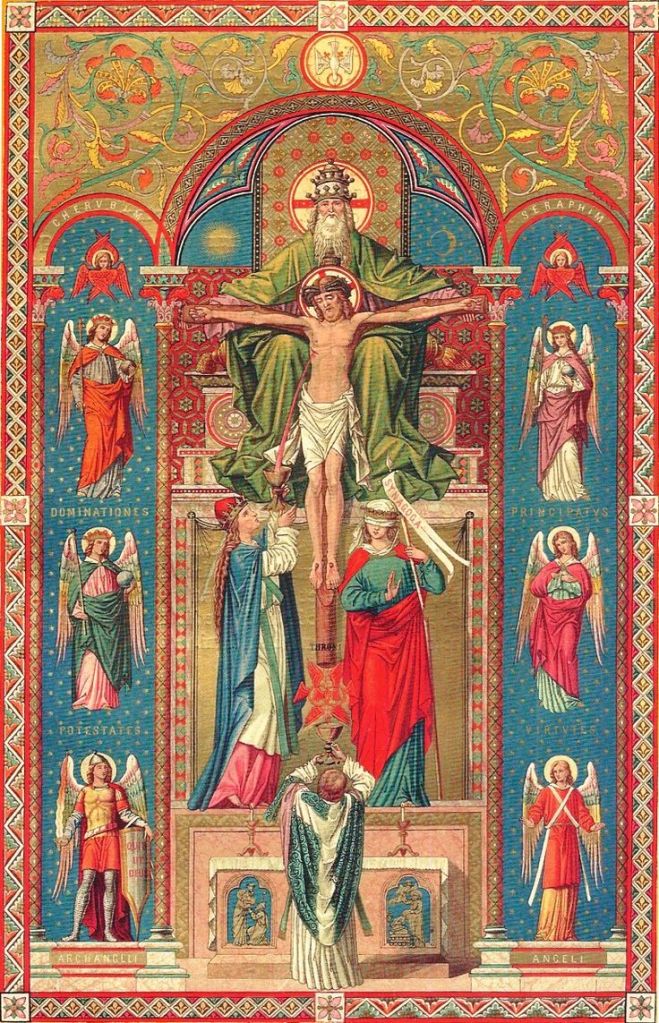

June is the month especially dedicated by the Church to the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Throughout this month the Church encourages devotions to the Sacred Heart. The Solemnity of the Sacred Heart almost always falls within June, unless Easter occurs very early in the year.[2] The human heart—whether your own, or Jesus’—is one of the chief metaphors that the Church uses in describing prayer. Perhaps very few of us have ever seen a human heart in person (as opposed to on TV). And unless you work in the medical field, you’ve probably never seen a beating human heart in person. Nonetheless, the living, beating human heart is something that everyone of us can understand because everyone of us has such a thing! We can even feel it at work if we quiet our self, and hold our hand against our heart.

The human heart is central to our natural lives. Similarly, our heart—spiritually speaking—is central to our supernatural lives. Regarding that supernatural life, it’s true that Scripture “speaks sometimes of the soul or the spirit” as its center, “but most often [Scripture speaks] of the heart (more than a thousand times). According to Scripture, it is the heart that prays. If our heart is far from God, the words of prayer are in vain.”[3] The question that sometimes leads us to fall away from prayer, or even at times to despair of prayer, is how—if our hearts are far from God—can that gap be bridged?

+ + +

In our Christian understanding of God, man, and man’s search for God, one of the most important truths is that “God calls man first. Man may forget his Creator[,] or hide far from His face; he may run after idols or accuse [God] of having abandoned him; [nonetheless,] the living and true God tirelessly calls each person to that mysterious encounter known as prayer.[4]

“In prayer, … God’s initiative of love always comes first; our own first step is always a response.”[5] Seeing this fact helps us return to the Little Flower’s description of prayer as “a surge of the heart.” That surge begins with God. God speaks within our heart, and moves our heart from within, because He created our heart along with all the rest of us.

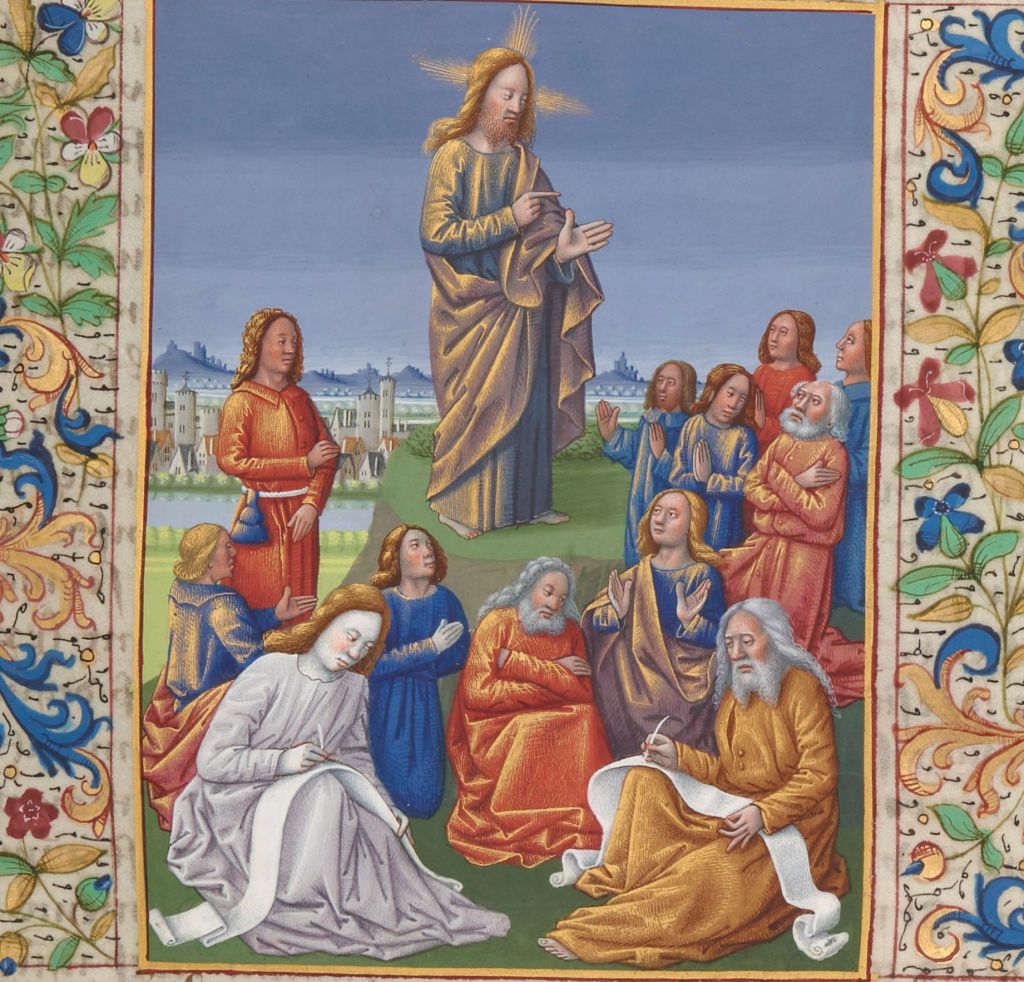

God always takes the initiative. One of the most beautiful verses in Scripture highlights this primacy of God. St. John, the evangelist and Beloved Disciple, wrote in his first epistle about the God who “is love”.[6] St. John said that “In this is love: not that we have loved God, but that He has loved us, and sent His Son as an expiation for our sins.”[7] God’s primacy—His initiative—colors every aspect of our spiritual life as Christians, and certainly the part of the spiritual life that we call prayer. Unfortunately, even though God always takes the first step, we often fail to take the second. Our readings today show us a major reason for this.

+ + +

In today’s First Reading we hear of a confrontation. At one end is King David. He’s one of the most dramatic figures in the Old Testament, and he’s one of the figures with whom we find it easiest to relate because he’s such a bundle of contradictions. He’s a person of strength, and he’s called by God to greatness, but he’s also a great sinner, and the consequences of his sins constantly run roughshod over his vocation.

The confrontation in today’s First Reading is between David and God, although Nathan is God’s prophet and it’s Nathan who confronts David on God’s behalf. Nathan doesn’t pull any punches. To illustrate just how sinfully David has acted, Nathan contrasts—on the one hand—the lofty vocation to which God had called David, with—on the other hand—David’s sinful response to God’s grace. God basically says through Nathan, “Look, David, I called you to the office of King of Israel. I gave you great power so that you could shepherd my flock. And what did you do with that power? Because you lusted after Bathsheba, you sent your military officer Uriah the Hittite to the front lines of battle, and then ordered that the rest of your troops quickly pull back, so that Uriah would be surrounded by enemy forces and killed, so that you could take his wife as your own.”

Now, the biblical author’s record of King David’s response is meager. The author of Second Kings only records David as replying with six very plain words: “I have sinned against the Lord.” Nonetheless, the context of this passage, much of which comes in the verses following our First Reading, make clear the depth of David’s contrition, sorrow, and remorse. Another book of the Old Testament also gives us some context for David’s very plain response.

King David is traditionally considered the composer of the Book of Psalms. He’s referred to as the book’s “composer” instead of as its “author” because, of course, the Psalms are songs, and were so from the beginning. David composed not just the words of the psalms, but their music, also (although his original music has been lost to history). Regardless, the point is that we can listen to any one of the 150 psalms and hear David speak his mind.

Today’s Responsorial Psalm fleshes out that very plain response of David to Nathan in the First Reading. Today’s Responsorial Psalm is selected verses from Psalm 32. The refrain: “Lord, forgive the wrong I have done.” As we hear the verses of this psalm, we can begin t0 see what was in David’s heart as he said before Nathan, “I have sinned against the Lord.” When Nathan confronted David with his sins of murder and adultery, David recognized that he had wounded his own soul by his sins, and needed the Lord to forgive the wrong he had done.

+ + +

Your sins weaken the powers of your soul, just as surely as a disease of the lungs affects your power to breath, which in turn affects the power of all the parts of your body to be nourished by the air around you. One of the powers of your soul that’s weakened by your sins is your ability to pray, with all the consequences that that entails in your spiritual life. Although it’s true that God always takes the initiative in our spiritual lives, including in our prayer, we often cannot perceive God at work in our hearts, because our sins weaken and even harden the human heart. Sin doesn’t weaken our ability to jabber away at God, but it does weaken our ability to hear Him, and if prayer on our end is supposed to be a response to God, we can be sure that if we’re not hearing Him to begin with, then whatever we may be saying, “the words of prayer are in vain.”[8]

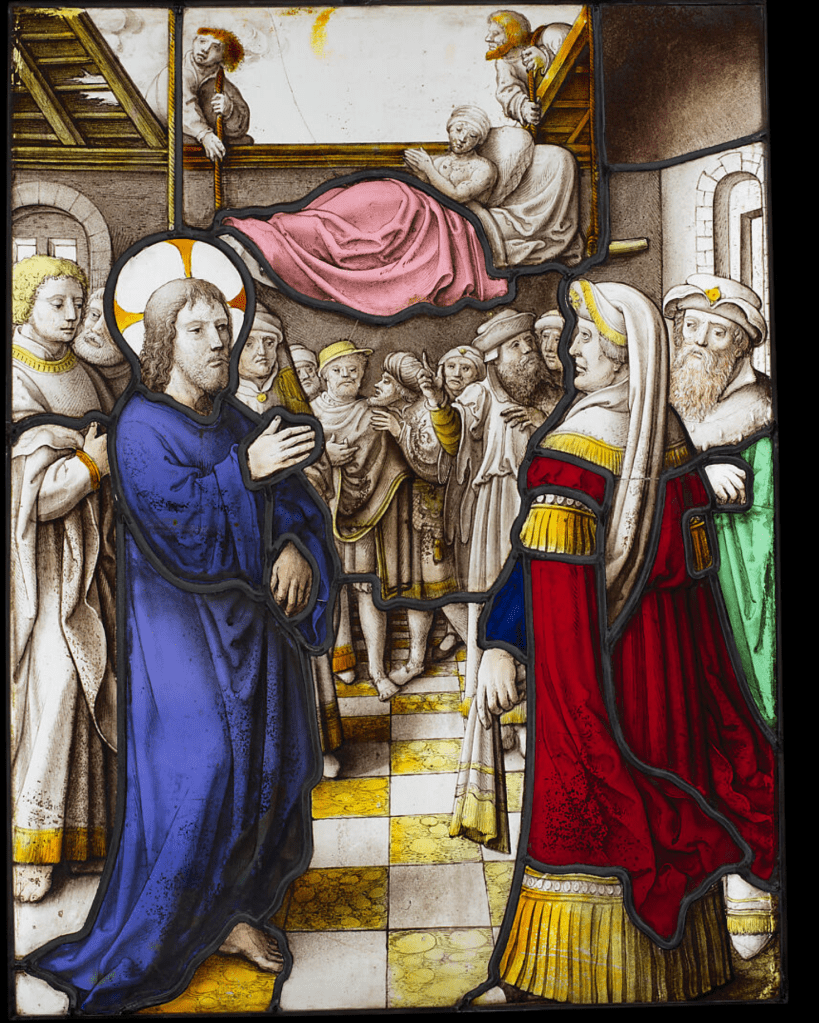

This is where you’re challenged to choose sides in the midst of another confrontation: the confrontation in today’s Gospel passage. While in the First Reading the conflict is among David, Nathan, and the Lord, in the Gospel Reading the conflict is among the “sinful woman”, Simon the Pharisee, and the Lord Jesus. However, there’s a profound difference between the two conflicts. In the Old Testament, the Lord uses the prophet to bring the sinner to Him. In the New Testament, the Lord uses the sinner to try to bring the Pharisee to Him. For your own spiritual life, to draw from this Gospel passage, you have to put yourself in the sandals of this sinful woman.

Until we look seriously at our sins, at their effects on our souls, and at their consequences (for ourselves and for others, both in this world and in the next), our experience of prayer will be diminished, and so therefore will the benefits of our prayer. Too often in our prayer we’re like Simon the Pharisee instead of being like the sinful woman. The Pharisee says to himself, “If [Jesus] were a prophet, he would know who and what sort of woman this is who is touching him, that she is a sinner.” By contrast, the sinful woman says nothing, but she acts with great love. The Pharisee speaks to himself with doubt about whether Jesus is even a prophet. But the woman acts with love towards Jesus, because she knows through faith that He is the Messiah who wants to wash away her sins.

If we wanted to sum up today’s Gospel passage, we could take away from church this weekend just those two sentences that Jesus proclaims to Simon: “her many sins have been forgiven because she has shown great love. But the one to whom little is forgiven, loves little.” In those words Jesus teaches us about the virtue of humility, which is the beginning of a fruitful prayer life, and through that prayer the beginning of the contentment and peace of mind that remain elusive until we remain in God.

[1] St. Thérèse of Lisieux, quoted in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC) #2558.

[2] The Solemnity of the Sacred Heart of Jesus fell during May in A.D. 2008.

[3] CCC #2562.

[4] CCC #2567.

[5] Ibid.

[6] 1 John 4:8.

[7] 1 John 4:10.

[8] CCC #2562.