The Exaltation of the Holy Cross

Numbers 21:4-9 + Philippians 2:6-11 + John 3:13-17

St. Anthony’s Catholic Church, Garden Plain, KS

September 14, 2025

In the Catholic Church, some feasts fall on the same date every year. St. Patrick’s Day, for example, is always March 17th. Christmas Day is always December 25th. The Assumption of our Blessed Mother is always August 15th.

Other feasts fall on a different date each year. These feasts include Easter Sunday, the First Sunday of Advent, and Pentecost.

Today the Church celebrates a feast that is always celebrated on September 14th. Because it’s always celebrated on that date, of course it rarely falls on a Sunday. So the average Catholic does not have many experiences of being at Mass on this feast day. That’s unfortunate, because today’s feast is like a magnifying glass that focuses our sight on the mystery of our Faith that’s at the heart of what it means to be saved.

+ + +

Today’s feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross has an historical background to it, apart from the historical event that took place on Good Friday atop Mount Calvary. The actual cross on which Jesus was crucified was lost for many years after the death and resurrection of Jesus. That’s not surprising, since pagan Rome ruled the Holy Land at the time that Jesus walked on this earth. The crosses were their “property”, which they used to kill those condemned as criminals.

However, some three hundred years after the events of Holy Week, the Roman Emperor Constantine became Christian, and by extension, the Roman Empire was—metaphorically—baptized. Saint Helena, the mother of Constantine, in the year 326 discovered the cross on which Jesus was crucified, and she found it in the tomb where Jesus had been buried.

So the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, which you can still visit today, was then built on the site where the cross was found. Today’s feast marks the dedication of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in 335. Although the building was consecrated on September 13, the next day in continuing ceremonies, the cross of Jesus was brought outside the church and raised high so that the faithful could pray before it. Then the faithful came forward to venerate it. If this sounds familiar, it’s because our Good Friday customs of the priest processing with and raising up a replica of the cross, and then the laity venerating the cross comes from that historical event in the fourth century. However, all that’s just historical background. The heart of today’s feast begins with what happened on Good Friday some two thousand years ago, and the means by which God achieved our salvation from sin.

+ + +

You know, one of the technologies that’s come to shape our world in recent years is drone technology. Like every human creation, this tech can be used for good or evil. In war, drones can be used by invading militaries to cause massive destruction and death.

But drones can also be used for beneficial purposes. For example, in business drones can help in the conduct of geographical surveys by giving a view of things from above. Likewise, you may have appreciated on a personal level drone footage taken of the Grand Canyon or the Mississippi River.

The perspective is what drones bring to the table. Drones help us to see a familiar sight from a new perspective.

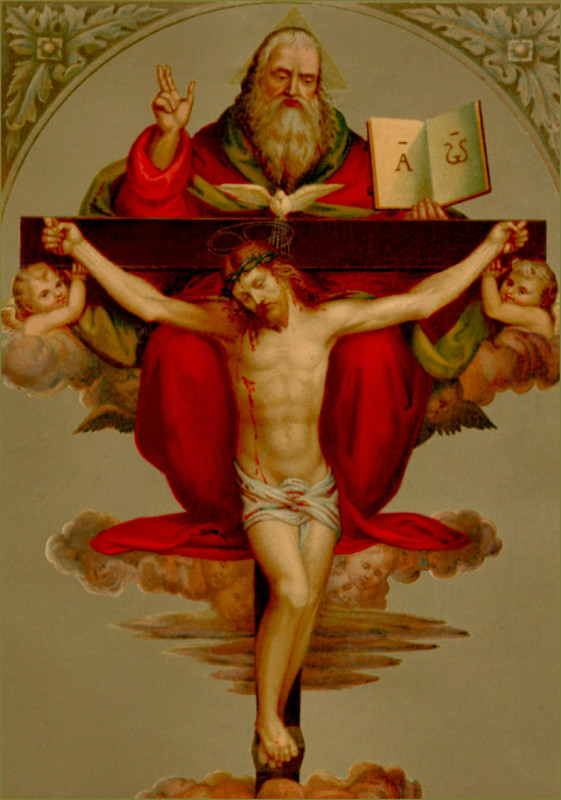

But have you ever seen drone footage of a church from above? It can be revealing. If you were to look, for example, at St. Peter’s Basilica in the Vatican, you would notice that the physical church building was designed and constructed in the shape of a cross. St. Peter’s Basilica has a head, two arms, and a long body, just like the crucifix that hangs in your home, and just like the crucifix that hangs in this church at the top of the high altar. Of course, only very large churches are large enough to be built in that shape, which is called “cruci-form”. However, it’s not only buildings that are meant to be formed in the shape of a cross.

+ + +

You are meant to be formed in the shape of a cross. You, as a Christian, are meant to be shaped by Christ into the shape of a cross. And you are meant to actively shape your life into the shape of a cross.

This doesn’t happen in a physical sense, of course. It happens when your thoughts, words, and actions reflect the love that Christ poured out from His Sacred Heart on the Cross on Good Friday. Jesus did not have to die on the Cross in order to redeem fallen man. Jesus is God, and so He is All-Powerful. He could have redeemed fallen man in any one of an infinite number of ways. But He chose to die on the Cross in order to forgive our sins. Jesus chose the Cross as the means of our salvation in order to reveal the depth of His love for fallen man, and He wants you to chose the Cross as the shape of your daily life.

+ + +

Now, no matter how old you are, whether nine or ninety, God is calling you right now to shape your life in the form of the Cross. Of course, you already make many sacrifices each day as part of your vocation: for many if not most of you, as spouses, parents, and grandparents. Yet in addition to those sacrifices of thought, word, and action that reflect the love of Christ from the Cross, there are other, very simple ways in which you can shape your daily life. I only have time to mention one of them, but if there were more time, I’d also speak about the simple prayer called The Sign of the Cross, and how important it is to pray it intentionally. I’d also speak, if I had more time, about the importance of having crucifixes that have been blessed in the main rooms of our homes.

However, since time is short, just consider Friday penance as one way of shaping your life in the form of the Cross. A lot of Catholics have never even been taught that every Friday of the year—not just during Lent—every Catholic is obligated to carry out some type of penitential sacrifice. In olden days, the Church specified what type of penance this was to be: that is, years ago, every Catholic every Friday of the year was obligated to abstain from eating meat.

Today, by contrast, each Catholic gets to decide what type of penitential sacrifice to carry out on a given Friday. It can be abstaining from meat, or praying the Stations of the Cross, or reading from one of the four Gospels the account of what happened on Good Friday. Nonetheless, regardless of which type of penance is chosen each week, every Catholic has the obligation each Friday to carry out some type of penitential sacrifice, in recognition of what Jesus sacrificed for us on Good Friday.

+ + +

God is eternal. He’s outside time, and so He has a divine perspective from which to see all of creation, and all of time, including what you and I call the past, the present, and the future. From this divine perspective, as God looks “down” from Heaven, He can see the shape of your life stretched out from the day you were conceived to the day on which you will die. He can see whether the shape of your life on this earth is the shape of the Cross. God asks a lot from you as a Christian. He sets the bar very high when it come to what He expects from you. To put it simply, He expects your life to reflect the life of Jesus. He expects the love in your heart to be the love of Jesus’ Sacred Heart. Of course, that’s not humanly possible unless God’s grace infuses your life, in order to empower your thoughts, words, and actions. God gifts us His grace through the Cross of Jesus Christ, and none of His graces are better suited to shaping our lives to the Cross than the graces of the Most Blessed Sacrament of the Eucharist.