The Second Sunday of Advent [A]

Isaiah 11:1-10 + Romans 15:4-9 + Matthew 3:1-12

references to the Catechism of the Catholic Church cited for today by the Vatican’s Homiletic Directory:

CCC 522, 711-716, 722: the prophets and the expectation of the Messiah

CCC 523, 717-720: the mission of John the Baptist

CCC 1427-29: conversion of the baptized

“A voice of one crying out in the desert, / Prepare the way of the Lord ….”

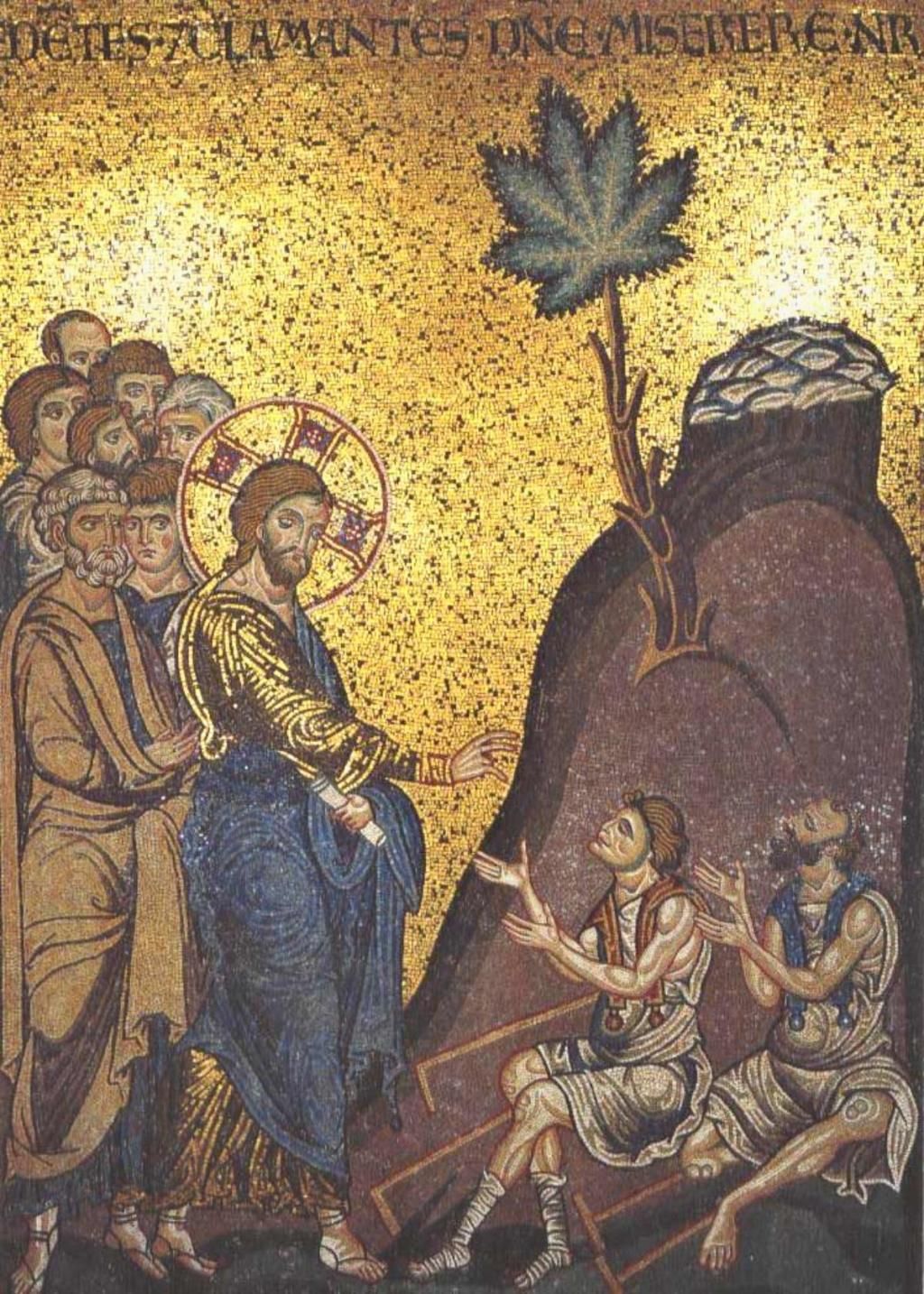

St. John the Baptist figures prominently in the Scripture passages that we hear during Advent. Of course, when St. John the Baptist speaks within these passages, he is an adult. He is the voice who prepares people for Jesus’ coming.

But John and Jesus were born only six months apart, so when John speaks about Jesus’ coming, he’s not speaking about the coming of Jesus’ birth at Bethlehem. In what way, then, does John’s preaching about Jesus’ coming connect to what the Season of Advent is all about?

We might say that the Season of Advent requires us to wear bifocals. We need help to shift our focus because there are two distinct objects for us to look at during Advent, and they stand far apart. (In fact, Advent also bears a third focus, but in this reflection, consider just the first two.)

We are tempted during December to look only for Jesus’ coming into the world at Bethlehem. The seasonal music and art that surrounds us narrows our focus to look only for the arrival of the baby Jesus within our fallen world.

Yet Jesus’ coming at Bethlehem was—merely, we might dare to say—a preparation. Jesus’ entrance into human history through His conception and birth were the condition that makes possible the fulfillment of a larger purpose. Jesus came into our fallen world so that He could come into each fallen soul in a unique manner.

Of course, God is all-powerful, so He can accomplish any goal He wills by any means He wills. God could have, for example, redeemed and sanctified fallen man without having to send His Son down from Heaven. God could have (metaphorically) snapped His fingers in Heaven, and man would have been redeemed.

Instead, the Father chose to redeem and sanctify fallen man by means of the conception, birth, death, and resurrection of His Son. God chose not to redeem and sanctify man from an infinite distance, but up close.

Jesus’ coming at Bethlehem makes possible the coming of Jesus that John the Baptist proclaims. At the start of this Sunday’s Gospel Reading, the evangelist notes that John was preaching in a desert. The point of John’s preaching is summed up by the first word recorded by the evangelist: “Repent!” Fallen man’s primary need is to repent.

The historical, geographical desert where John preached symbolizes the state of fallen man’s soul. The soul of fallen man is dry and barren. Little grows in a desert, and in the fallen soul the virtues cannot flourish as God designs.

Nonetheless, God wills to enter the desert of the human soul in the flesh. John entered an earthly desert as a voice crying out, but the Word became flesh so that He might dwell in the desert of the fallen soul, and from within redeem and sanctify it. The Word made Flesh, when He is admitted into a human soul, makes divine grace and human virtues flourish there. Perhaps that is why on the morning of the Resurrection, the disciple Mary mistakes the Risen Lord for the gardener.

This line of reflection may seem to be taking us far from the spirit of Advent. In fact, it points out the trajectory across which Advent points our attention, towards the second focus of the season. Advent and Christmas, as paired seasons, are the Church’s preparation for Lent and Easter. Christ’s birth at Bethlehem makes possible His death on Calvary. Even now during Advent, the Church focuses our attention on this over-arching trajectory through John’s preaching.

The connections between these pairs of seasons—Advent/Christmas and Lent/Easter—reveal one reason why Advent is a penitential season. The preaching of John the Baptist—both its setting of a desert, and its command to repent—is another reason why Advent is a penitential season.

Of course, we go to Confession not chiefly to confess our sins, but chiefly to receive absolution. Nonetheless, confession must precede absolution, and repentance must precede confession.

Jesus’ coming into our world at Bethlehem is a miracle of human history, changing the world for all time. But Jesus’ coming into the soul of a sinner to redeem and sanctify him is a miracle of grace which bears eternal consequences. The journey of a human sinner into eternally abiding within the presence of God begins with a single word: “Repent!”