The Third Sunday of Lent [A]

Exodus 17:3-7 + Romans 5:1-2,5-8 + John 4:5-42

St. Anthony’s Catholic Church, Wellington, KS

March 8, 2026

This year on the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Sundays of Lent, our Gospel passage comes from the Gospel according to Saint John. Saint John’s Gospel account differs from Matthew, Mark, and Luke in many ways. One of the unique things about John, which we will notice during these three Sundays, is that John often expresses double meanings through Jesus’ words and actions.

For example, when Jesus cures a blind man, the evangelist goes out of his way to show how that cure—besides being a physical healing—is also a sign that Jesus can cure a person’s spiritual blindness. Also, in John Jesus speaks with Nicodemus late at night about being “born again”, which Nicodemus misunderstands. Nicodemus goes on and on thinking that Jesus is talking about being physically “born again”, when Jesus is talking about being spiritually born again. In fact, most of the double meanings in John occur when people confuse the worldly and the heavenly. To be honest, that’s a lot like our lives as sinners: we confuse the worldly and the heavenly, putting our focus and attention in life in the wrong place. St. John is trying to shift our attention in the right direction.

So in today’s Gospel passage, St. John the Evangelist describes Jesus as He’s approaching the Samaritan town where Jacob’s well is found. Jesus is “tired from His journey”, and so He sits down at the well. The evangelist also notes that “it was about noon”, implying that Jesus—in His sacred humanity—was tired and hot and thirsty. Jesus is like us in all things but sin. His human body needed water just as yours does. That’s why on Good Friday as He was dying on the Cross, Jesus cried out, “I thirst”.[1] Only St. John the Evangelist records Jesus as saying that on the Cross: Matthew, Mark, and Luke do not. For St. John, Jesus saying “I thirst” on the Cross ties into the other teachings that the evangelist records in his Gospel account, especially today’s Gospel Reading.

Jesus, through His human need for water, leads the Samaritan woman to see that she also needs something. Here’s where the double meaning in this passage starts to unfold. Only a few verses at the start of today’s Gospel passage are a discussion about a drink of water for Jesus’ physical thirst. After those first few verses, Jesus shifts the attention away from Himself, and away from His physical need. He shifts the attention towards the Samaritan woman, and toward her spiritual need.

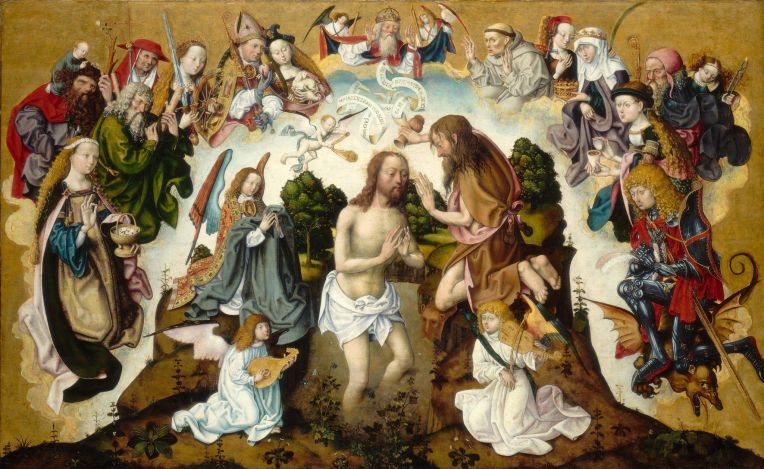

The spiritual thirst that Jesus describes is one that only He can provide water for. The spiritual water that Jesus offers, He calls “living water”. In the physical world, water is not “living” in the way that a plant or animal is. Nonetheless, the spiritual water that flows from Jesus does bear life. This spiritual water flows from Jesus through two of the sacraments that Jesus gave as gifts to His Church: the Sacrament of Baptism, and the Sacrament of Confession. The Sacraments of Baptism and Confession are similar in many ways, all of which can help us appreciate the Good News that Jesus is sharing with the Samaritan woman in today’s Gospel passage. Both Baptism and Confession cause three changes in the person who receives them devoutly.

+ + +

In both the Sacrament of Baptism and the Sacrament of Confession, the person is first of all washed clean of sin. In Baptism, the waters wash away all sin: both Original Sin, and (if the newly baptized is older than the age of reason) any actual sin committed by that individual.

Unfortunately, many people—even many baptized Christians!—only think about Baptism in terms of having sins washed away so that they can get to Heaven. They stop there when they think about Baptism. They think of Baptism only in terms of getting to Heaven. Getting to Heaven, of course, is one part of why we’re baptized: in fact, it’s the ultimate reason; but it’s not the only reason. That reduction of Baptism is what led many in the early Church to delay their own baptism until they were on their deathbed, so that they could be more sure of getting into Heaven!

It’s easy to see how self-focused this kind of thinking is: that I receive God’s grace for me, in order to get me into Heaven. But Jesus did not give His life for us, so that we would make our spiritual life about our self. Instead, Jesus gave His life for us, so that we would give our lives for others. Thinking that Jesus gave His life for us, so that we could make our life about our self is how the world thinks. Jesus is trying to shift our attention to the heavenly way of thinking: so that we would live by Christ’s words that, “whoever wishes to save his life will lose it, [while] whoever loses his life for [Jesus’] sake…will save it”.[2]

Similar to the Sacrament of Baptism, in a sincere, valid Confession, all personal sins—mortal and venial—are washed away. Yet many Catholics reduce the practice of Confession to only one aim: just getting to Heaven, or even just staying out of hell. That’s why many Catholics only go to confession when they’ve committed a mortal sin. But is Confession only for washing away past sins?

+ + +

The second change in the person who receives the Sacrament of Baptism or Confession is a preparation for the future. Not just our future in Heaven, but also our future on earth: however many days, months, and years that might remain for us here on earth. In both Baptism and Confession, God washes something away from our souls: namely, sin. But He also infuses graces into our souls, for the sake of a stronger life on earth.

At the moment of your baptism, when God washed sin away from your soul, He put in your soul the graces of the three supernatural virtues: faith, hope, and charity. God gave these to you not only to help you get to Heaven, but also to change the shape of your earthly life.

Similarly, in Confession, when God washes sin away from your soul, He infuses into your soul the divine gift that the Church calls “sacramental grace”. The graces from Confession give you, in the words of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, “an increase of spiritual strength for the Christian battle”.[3] What does the “Christian battle” involve? Consider just two its demands.

One of the more challenging demands of the “Christian battle” is standing strong in the face of temptation. The Gospel Reading on the First Sunday of Lent described Jesus spending forty days in the desert being tempted. We are like Jesus in facing temptation, but we are much weaker than Jesus Christ. However, the graces from the Sacrament of Confession strengthen us for that “Christian battle” against temptation.

Another challenging demand of the “Christian battle” is forgiving others in a Christ-like manner. When someone has deeply wronged us—especially someone in our family—there’s a temptation to whitewash over it. We’re tempted to just mouth the words “I forgive you” without really meaning it in order to avoid dealing with the problem in a serious way. Often we do this because it’s just too demanding to get into the weeds and really face everything involved in both the sin that caused the problem, and the reconciliation that’s truly needed. So we just punt, and mouth the words “I forgive you.” That’s not how Jesus forgave on the Cross. He put His entire Self into the reconciliation of God and man, and the graces from Confession strengthen us to forgive others in the way that Jesus did on Calvary.

This latter example of the “Christian battle” leads into the third change that Baptism and Confession bring about. This change is also illustrated in today’s Gospel Reading. This passage is not just about the two persons engaged in dialogue, although at first the Samaritan woman might think so, just as you and I might think that our lives as Christians are about our selves. This passage is also about those whom the evangelist mentions at the end of this Gospel Reading: those who “began to believe in [Jesus] because of the word of the woman who testified.”

+ + +

Those words at the end of today’s Gospel passage illustrate the third change that Baptism and Confession bring about within the Christian soul. The third change relates to being part of something larger than your own self. In Baptism, this took place through God the Father’s adoption of you, which joined your life to the lives of your brothers and sisters in Christ. In Confession, you are reconciled with both your God and your neighbor. In the life of the Samaritan woman, this took place through the testimony that she gave to others because of the “living water” that she drank.

So here we can see the problem with “deathbed baptisms”. What if the Samaritan woman in today’s Gospel passage had avoided Jesus all her life, and had waited until the end of her earthly life to drink of that “living water”? How many people around her never would have heard her testimony, and therefore never would have come to Jesus? The longer we wait to allow Jesus’ living waters into our lives, the longer it will be before we can be an instrument of God’s grace, helping others who may have no other way of learning more about Jesus except through our words and actions.

[1] John 19:28; cf. Psalm 69:21.

[2] Mark 8:35.

[3] Catechism of the Catholic Church 1496.