The Twenty-second Sunday in Ordinary Time [C]

Sirach 3:17-18,20,28-29 + Hebrews 12:18-19,22-24 + Luke 14:1,7-14

St. Anthony’s Catholic Church, Garden Plain, KS

August 31, 2025

During the three years leading up to His Passion and Death, Jesus taught throughout the Holy Land. All four of the Gospel accounts show Jesus as a teacher, but St. Matthew in his Gospel account highlights Jesus’ teaching.

Sometimes Jesus teaches by means of short parables, and at other times by long sermons. The first and greatest of Jesus’ sermons is His Sermon on the Mount, which takes up three of the 28 chapters of St. Matthew’s account of the Gospel. This sermon, which you can find in Chapters 5, 6 and 7 of Matthew, makes for excellent spiritual reading.

Jesus, like any good teacher, knows that a teacher’s first words are key. The first words that a teacher speaks to his students—at the start of a school year, or on any given morning when class begins—can set the tone and set the stage for all that’s going to be taught. Jesus makes use of this principle.

So what are the very first words that Jesus speaks in His first and greatest public sermon, the Sermon on the Mount? “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for the Kingdom of Heaven is theirs.”[1]

These words are the foundation of Jesus’ teaching, upon which the rest of the Sermon on the Mount is built. And since the Sermon on the Mount is the greatest of Jesus’ sermons, you could argue that these words are the foundation of all Jesus’ teachings: “Blessed are the poor in spirit, for the Kingdom of Heaven is theirs.”

+ + +

So what exactly is Jesus referring to when He talks about being “poor in spirit”? What does your daily life look like if you are “poor in spirit”? The fourth-century bishop St. Gregory of Nyssa explained that when Jesus preached about “poverty in spirit”, He was speaking about humility. Specifically, St. Gregory wrote that Jesus “speaks of voluntary humility as ‘poverty in spirit’; the Apostle [Paul] gives an example of God’s poverty when he says: ‘For your sakes He became poor.’” [2]

So the key to reflecting upon today’s Scriptures is that humility is a kind of poverty.

In that quote of St. Gregory there are two points to help us focus on today’s Scriptures.

+ + +

The first point is to recognize the importance of the word “voluntary”. Jesus teaches us that voluntary humility is poverty of spirit. Jesus is not speaking about the kind of humility that’s forced upon us. Poverty in spirit is only the kind of humility that we freely choose.

In today’s Gospel passage, “Jesus went to dine at the home of one of the leading Pharisees”. It’s interesting: at this home, everyone is observing everyone else. The evangelist tells us that, on the one hand, “the people there were observing [Jesus] carefully”. But on the other hand, Jesus tells His parable “to those who had been invited” because Jesus had noticed “how they were choosing the places of honor at the table”. They were choosing, not humility, but humility’s opposite: self-promotion.

Within Jesus’ parable, He shows us how there are two kinds of humility. Jesus begins by describing the kind of humility that’s forced upon oneself. Jesus describes someone seating himself “in the place of honor”, and then being forced by the host to embarrass himself by moving down to “the lowest place”. This is what’s called “humble pie”: involuntary humility. Life serves up to each of us lots of helpings of humble pie. Humble pie is not the humility that Jesus wants us to cultivate, although we can respond to humble pie in a virtuous manner.

But then, Jesus describes the kind of humility that can be virtuous when we cultivate it. What does Jesus tell us to do? “[T]ake the lowest place[,] so that when the host comes to you[,] he may say, ‘My friend, move up to a higher position.’” In other words, practice the virtue of voluntary humility. Don’t get frustrated with how often life serves you “humble pie”. Take the initiative: practice the virtue of voluntary humility, and you’ll find yourself eating much less humble pie, or at least, having less spiritual indigestion from the humble pie that life serves you.

+ + +

Still, even if we understand the need to practice humility voluntarily, there’s a problem. It’s very difficult to do. As in Jesus’ parable, there’s often embarrassment connected to acting humbly. To take the initiative of voluntary humility is difficult. To humble oneself before, not only God, but also others is difficult. How can we overcome the difficulties connected with acting humbly?

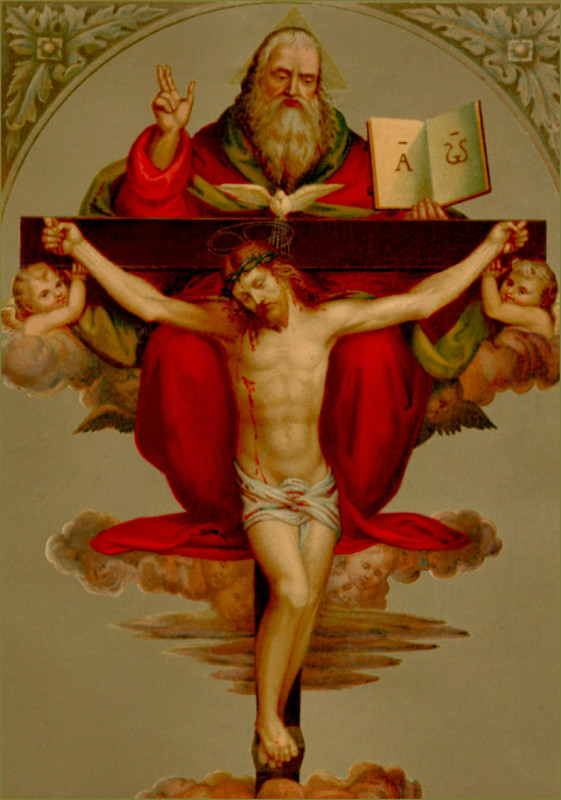

The answer, of course, is Jesus. The Apostle Paul gives us an example of God’s own voluntary poverty when Paul says to the Corinthians: “For your sakes [Jesus] became poor.” St. Paul is referring to God the Son leaving the riches of the Kingdom of Heaven, and entering our poor world within the womb of the Blessed Virgin Mary, assuming our frail human nature. In terms of His human life, this was Jesus’ first act of voluntary humility. We meditate on this first act of humility in the First Joyful Mystery of the Rosary: the Annunciation.

But of course the reason that Jesus entered our sinful world was to offer His Body and Blood, soul and divinity for us on Calvary. We meditate on this second act of humility in the Fifth Sorrowful Mystery of the Rosary: the Crucifixion.

So Jesus gave us two great examples of humility: both being conceived at the Annunciation, and dying on Calvary; both becoming human, and offering His humanity on the Cross. But how could you or I possibly be strong enough to imitate such examples? The answer is a third example of humility that Jesus offers us.

Maybe we ought to recall the rest of that verse from Second Corinthians that St. Gregory of Nyssa quotes. Here’s the entire verse:

“For you know the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ[:] that though He was rich, yet for your sake He became poor, so that by His poverty you might become rich.”

It’s not the mere example of Jesus’ poverty that makes you rich. It’s by entering into Jesus’ life—His Body and Blood, soul and divinity—that you become rich in God’s grace. Only this grace can make you strong enough to practice the virtue of humility on a par with Jesus’ own humility. This is only possible through the Eucharist, which Jesus instituted at His Last Supper. We meditate on this third act of humility in the Fifth Luminous Mystery of the Rosary: the Institution of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass at Jesus’ Last Supper, where the Son of God takes bread and wine and changes them into His very Self.

In today’s First Reading, Sirach counsels you to “[h]umble yourself the more, the greater you are”. Through Baptism, you are a child of God. So indeed you are. That is a profoundly great vocation: a demanding one. To be faithful to that vocation, your humility must be the humility of God’s only-begotten Son. Thanks be to God, He has called you as His child to the head of the Banquet Table of the Eucharist, to devoutly and humbly receive Jesus’ own life, so that He might truly live in you, and through each of your thoughts, words, and actions.

_______________________________________________

[1] Matthew 5:3.

[2] Catechism of the Catholic Church 2546, quoting St. Gregory of Nyssa, De Beatitudinibus 1; cf. 2 Corinthians 8:9.